Westward Migration

The members of the Donner Party were among the wave of emigrants who would bring the US its manifest destiny

to stretch from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Reports from California settlers, including John Sutter, a Swiss who had a fort

at the confluence of the Sacramento and American Rivers (present Sacramento) and John Marsh, who had a ranch near Mt. Diablo, described the excellent climate, the ease of farming and the weakness of the Mexican government. These reports encouraged emigration from the economically depressed and malaria-ridden Mississippi Valley.

Several books published by 1845 described the trail to California. The books’ glowing description of life in California, and the trail information, seemed to provide all one needed to know to make the crossing. Approximately 2,700 people set out on the Trail in 1846. About 1,500 traveled to California, the rest to Oregon.

The Establishment of the California Trail

The trail to California had been established not by the government, but by members of the Emigrant Societies

formed in the 1840’s. The efforts of three parties had established a passable wagon road over the two main obstacles: the Great Salt Lake Desert in Utah, and the Sierra Nevada mountains in California. The result was a journey of 2,000 miles in a single summer and fall, by oxen or horses at 15 miles a day, which meant a voyage of about five months.

Modified from material Copyright (c) 1994 MAGELLAN Geographix, Inc.

The first wagon road to California was the old Spanish trail through Santa Fe to Los Angeles. The first trail to Oregon was Lewis and Clark’s route along the upper Missouri River to the Columbia River. But resistance from the tribes in the 1820s led fur trappers to use a trail along the North Platte River, crossing the Rockies at South Pass. From there the trappers reached the Hudson Bay Company’s Fort Hall on the Snake River.

The trappers explored from the Great Salt Lake, over the Nevada desert all the way to California. In the Spring of 1828, Jedediah Smith returned from California by crossing the Sierra near the present Ebbetts Pass.

In 1841 the Bartleson-Bidwell Party became the first emigrants to attempt a wagon crossing. The wagons in the Party split off from the trappers’ trail to Oregon at Soda Springs before reaching Fort Hall. They headed south down the Bear River and then west along the north shore of the Great Salt Lake. Crossing the desert west of the lake they were forced to abandon their wagons. Accompanied by their surviving animals, they eventually found the Mary’s River (now the Humboldt) and followed it to its sink (near present Lovelock, Nevada). Crossing the desert to the south, they reached the Walker River, which they ascended over the Sierra in the same region crossed by Jedediah Smith in 1828.

In 1843, the Oregon Trail was finally established as a wagon road, following the route of the Bartelson-Bidwell Party members who had gone to Oregon in 1841. You can learn about the Oregon Trail from the makers of the PBS film.

In 1843, a party formed by Joseph Chiles of the Bartleson-Bidwell Party set out for California. The wagons were led by the trapper Joseph Walker along the Oregon Trail to Fort Hall and then south and west along an old trapper’s trail to the wells at the head of the Humboldt River (present Wells, NV). From the sink of the Humboldt, Walker led the wagons towards a pass at the south end of the Sierra that he had crossed in 1834. Near present Owens Lake they were forced to abandon their wagons and cross the Sierra by pack train.

In 1844, the Stephens-Townsend-Murphy Party, guided by the old mountain man Caleb Greenwood, followed the Oregon Trail a few days’s travel further past Fort Hall before heading south along the Raft River and picking up the trapper’s trail to the Humboldt River. At the sink by October, they relied on a Paiute named Truckee who led them west forty miles across a desert to a river (now called the Truckee) that flowed from a small lake at the foot of the Sierra. A pass at its west end, some 1,200 feet high, led over the Sierra. The party left six wagons at the lake, and the rest in a high valley west of the pass. In the Spring they recovered all the wagons, and thus established the first wagon road to California.

Truckee’s Lake (now Donner Lake)

In 1845, a lawyer named Lansford W. Hastings published The Emigrant’s Guide to Oregon and California based on his travels to Oregon in 1842, and California in 1843. Not knowing of the Stevens Party’s passage, Hastings wrote that emigrants to California could leave the Oregon Trail before Fort Hall and head towards the Great Salt Lake to cut off several hundred miles. At the time he wrote his book, he had not traveled that route, but he made the crossing on horseback in the Spring of 1846 when he headed east to meet the emigrants. According to James Clyman who accompanied Hastings, Hastings was looking for some force from the states with which it was designed to revolutionize California.

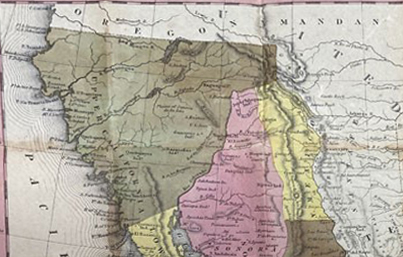

When the Donner Party set out 1846, despite decades of exploration, there was still much misinformation about the route west, including hoped-for river routes from the Great Basin to the Pacific Ocean. Based on erroneous reports from Spanish missionaries in the 1780s, mapmakers showed these rivers and explorers tried in vain to find them. An 1846 map of Mexico by Samuel Mitchell, with details copied from an 1822 map of North America by Henry Tanner, shows the Rio Buenaventura flowing from a Salt Lake

to the California Central Coast, and the Rio Timpanagos flowing from Lake Timpanagos (Great Salt Lake) to the San Francisco Bay.

1846 Map of Upper California by Samuel Mitchell