September 1846

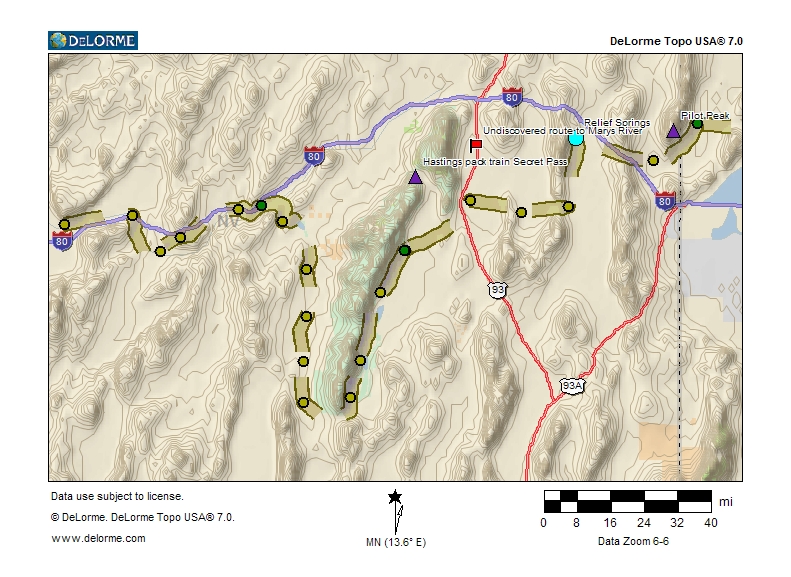

The Donner Party traveled from the western edge of the Great Salt Desert (near the present Utah-Nevada border) to Mary’s River (now the Humboldt River) where they re-jointed the the more established California Trail (at present Hunting Siding, Nevada).

The dated entries below are from the diary of Hiram Miller and James F. Reed. The Diary is controversial to some historians. The existence of the diary was not known until the estate of Martha (Patty) Reed donated it to Sutter’s Fort Historical Museum in 1945. Apparently neither Virginia nor Patty revealed the diary to McGlashan. Virginia apparently did not use it as a source for her Century Magazine article in 1891. Some of the entries appear to have been written after the events, which led both Stewart and King to question it. King went so far as to suggest that some entries may have been written after Reed arrived in California, which seems unlikely.

Tuesday, September 1, 1846

Tusdy Sept 1 in desert

The Trail left the Gray Back Hills, and crossed the salt flats towards Floating Island at the north end of the Silver Island Mountains, passing Floating Island on the north, and crossing a low pass (now called Donner-Reed Pass) between the Silver Island Mountains and Crater Island Range.

The crossing of the salt desert was a fantastic experience. Thornton recorded a common optical illusion on the bright white salt, as told by Eddy:

They saw themselves, their wagons, their teams, and the dogs with them, in very many places, while crossing this plain, repeated many times in all the distinctness and vividness of life. Mr. Eddy informed me that he was surprised to see twenty men all walking in the same direction in which he was traveling. They all stopped at the same time, and the motions of their bodies corresponded. At length he was astounded with the discovery that they were men whose features and dress were like his own, and that they were imitating his own motions. When he stood still, they stood still, and when he advanced, they did so also. ... Subsequently he saw the caravan repeated in the same extraordinary and startling manner.Modern travelers can see this same phenomena as they drive along Interstate 80. If they look north across the salt flats, they can see what appears to be cars and trucks driving on a road through the desert parallel to the Interstate. The construction of the dike at the south end of the Newfoundland Evaporation Basin has reduced the areas where travelers on the highway can see out into the salt flats. <> Thirteen year old Virginia Reed described the crossing in a letter to her cousin Mary Keyes, dated May 16, 1847: Speaking of the people at Bridger’s Fort, she wrote:

they pursuaded us to take Haistings cut off over the salt plain they said it saved 3 Hondred miles, we went that road & we had to go through a long dry drive of 40 miles With out water or grass Hastings said it was 40 but i think it was 80 miles We traveld a day and night & a nother day and at noon pa went on to see if he Coud find Water, he had not been gone long till some of the oxen give out and we had to leve the Wagons and take the oxen on to water one of the men staid with us and the others went on with the cattel to water

James Reed edited his step-daughter’s letter before she mailed it, and provided the following details. The men who stayed with the family were Walter Herron & Bailos

and those who drove the cattle were boys Milt Elliot & J Smith.

Most emigrants were forced to leave their wagons on the desert and drive their cattle to water before they gave out. James Mathers, who crossed with the Harlan-Young party under the guidance of Lansford Hastings two weeks before the Donners, wrote in his diary: 16th Started on the long drive and after traveling until near the middle of the next day without resting but a little we were obliged to leave two waggons and go on with the third so as to get the cattle to water the sooner, the distance still being more than 20 m.

Wednesday, September 2, 1846

Wed 2 in do Cattle got in Reeds Cattle lost this night

Virginia’s May 16, 1847 letter continues: pa was a coming back to us with Water and met the men thay was about 10 miles from water pa said they get to water that night, and the next day to bring the cattel back for the Wagons any bring some Water

The advance part of the Donner Party reached the springs at Pilot Peak by leaving their wagons on the desert, and driving their cattle to the water, as recorded by Thornton:

at about ten o’clock A.M. of the [third day], Mr. Eddy and some others succeeded, after leaving his wagons twenty miles back, in getting getting his team across the Great Salt Plains, to a beautiful spring at the foot of a mountain on the west side of the plain, and distance about eighty miles from their [last] camp.... On the evening ..., just at dark, Mr. Reed came up to them, and informed them that his wagons and those of Messrs. Donner had been left about forty miles in the rear, and that the drivers were trying to bring the cattle forward to water. After remaining about an hour, he started back to meet the drivers with the cattle, and to get his family. Mr. Eddy accompanied him back five miles, with a bucket of water for and ox of his that had become exhausted, in consequence of thirst, and had lain down.

James Reed remembered the events in his article in the Pacific Rural Press in 1871:

We started to cross the desert traveling day and night only stopping to feed and water our teams as long as water and grass lasted. We must have made at least two-thirds of the way across when a great portion of the cattle showed signs of giving out. Here the company requested me to ride on and find the water and report. Before leaving I requested my principal teamster, that when my cattle became so exhausted that they could not proceed further with the wagons, to turn them out and drive them on the road after me until they reached the water, but the teamster misunderstanding unyoked them when they first showed symptoms of giving out, starting on with them for the water. I found the water about twenty miles from where I left the company and started on my return. About eleven o’clock at night, I met my teamsters with all my cattle and horses. I cautioned them particularly to keep the cattle on the road, for that as soon as they would scent the water they would break for it. I proceeded on and reached my family and wagons. Some time after leaving the man one of the horses gave out and while they were striving to get it along, the cattle scented the water and started for it. And when they started with the horses, the cattle were out of sight, they could not find them, or their trail, as they told me afterward.

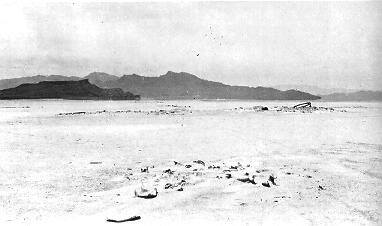

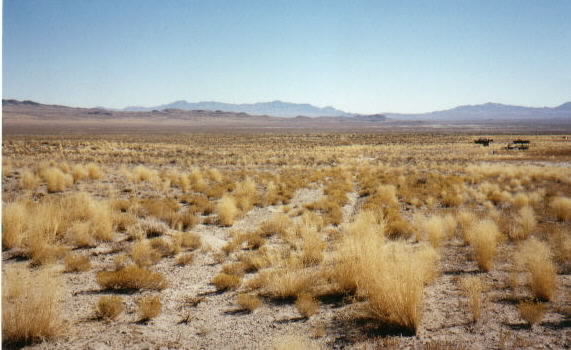

The Salt Desert from Floating Island, looking east to the Grayback Hills, photographed 1999

The Salt Desert from Floating Island, looking west to Silver Island Mountains, photographed 1999

Thursday, September 3, 1846

Thusdy 3 in do some teams got in

The Trail ended at the springs at the base of the prominent Pilot Peak. These springs are now called Donner Spring, and are located on the Stephens ranch about 25 miles north of Wendover, Nevada. For a description of the springs and the ranch, see Colin Gilboy’s Donner Spring web page.

According to Thornton, The Messrs. Donner got to water, with a part of their teams, at about 2’oclock, A.M....

Virginia’s May 16, 1847 letter continues:

pa got to us about noon [Reed crossed outnoonand wrotedaylight next morning] the man that was with us took the horse and went on to water We wated thare throug [Reed added:thinking they would] come we wated til night and We thought we start and walk to Mr doners wagons that night [Reed addeddistance 10 miles] we took what little water we had and some bread and started pa caried Thomos and all the rest of us walk we got to Donner and they were all a sleep so we laid down on the ground we spread one shawl dowon we laid down on it and spred another over us and then put the dogs on top it was the couldes night you most ever saw the wind blew and if it haden bin for the dogs we would have Frosen

Forty-five years later, Virginia’s memory of that night was just as strong, as told in her article for Century magazine:

Can I ever forget that night in the desert, when we walked mile after mile in the darkness, every step seeming to be the very last we could take? Suddenly all fatigue was banished by fear: through the night came a swift rushing sound of one of the young steers crazed by thirst and apparently bent upon our destruction. My father, holding his youngest child in his arms and keeping us all close behind him, drew his pistol, but finally the maddened beast turned and dashed off into the darkness.

Reed recounted the events in his 1871 article in the Pacific Rural Press:

I staid with my family and wagons the next day, expecting every hour the return of some of my young men with water, and the information of the arrival of the cattle at the water. Owing to the mistake of the teamsters in turning the cattle out so soon the other wagons had drove miles past mine and dropped their wagons along the road, as their cattle gave out, and some few of them reaching water with their wagons. Receiving no information and the water being nearly exhausted, in the evening I started on foot with my family to reach the water. In the course of the night the children became exhausted. I stopped, spread a blanket and laid them down covering them with shawls. In a short time a cold hurricane commenced blowing; the children soon complained of the cold. Having four dogs with us I had them lie down with the children outside the covers. They were then kept warm. Mrs. Reed and myself sitting to the windward helped shelter them from the storm. Very soon one of the dogs jumped up and started out barking, the others following making an attack on something approaching us. Very soon I got sight of an animal making directly for us; the dogs seizing it changed its course, and when passing I discovered it to be one of my young steers. In cautiously stating that it was mad, in a moment my wife and children started to their feet scattering like quail, and it was some minutes before I could quiet camp; there was no more complaining of being tired or sleepy the balance of the night.

Donner Springs, looking east to Donner-Reed Pass, photographed 1999

Friday, September 4 1846

Fridy 4 in do lost Reeds Cattle 9 Yok by not driving them Carefule to water as directed by Reed-- Hunting Cattle 3 or 4 days the rest of teams getting in and resting Cattle all nearly given out

Virginia’s May 16, 1847 letter continues:

as soon as it was day we went to Miz Donners she said we could not walk to the Water and if we staid we could ride in thare wagons to the spring so pa went on to the water to see why they did not bring the cattel when he got thare thare was but one ox and cow thare & none of the rest had got to Water Mr Donner come out that night with his cattel and brought his Wagons and all of us in

In his 1871 memoirs, James Reed wrote:

We arrived about daylight at the wagons of Jacob Donner, and the next in advance of me, whose cattle having given out, had been driven to water. Here I first learned of the loss of my cattle, it being the second day after they had started for the water. Leaving my family with Mrs. Donner, I reached the encampment. Many of the people were out hunting cattle, some of them had got their teams together and were going back into the desert for their wagons. Among them was Mr. Jacob Donner, who kindly brought my family along with his own to the encampment.

Saturday, September 5, 1846

Sat 5 Still in Camp in the west Side of Salt Desert

In his 1871 memoirs, Reed described the search for his cattle:

We remained here for days hunting cattle, some of the party finding all, others a portion, all having enough to haul their wagons except for myself. On the next day or day following, while I was out hunting my cattle, two Indians came to the camp, and by signs gave the company to understand that there were so many head of cattle out, corroborating the number still missing; .... The next morning, in company with young Mr. Graves--he kindly volunteering--I started in the direction the Indians had taken; after hunting this day and the following, remaining out during the night, we returned unsuccessful, not finding a trace of the cattle.

Reed was wrong about being the only one who couldn’t retrieve his wagons. As noted by Thornton, from Eddy’s recollection: George Donner had lost one wagon. Kiesburg also lost a wagon.

Sunday, September 6, 1846

Sond 6 Started for Reeds waggons lying in the Salt Plains 28 miles from Camp Cached 2 waggs and effect

In his 1871 memoirs, Reed described the cache of the wagons after giving up the search for his cattle:

I now gave up all hope of finding them and turned my attention to making arrangements for proceeding on my journey. In the desert were my [three] wagons; all the team remaining was an ox and a cow. There was no alternative but to leave everything but provisions, bedding and clothing. These were placed in the wagon that had been used for my family. I made a cache of everything else.

Thirteen-year old Virginia Reed described the search for the cattle, and the cache of the wagons, in her letter of May 16, 1847:

we staid thare a week and Hunted for our cattel and could not find them so some of the companie took thare oxen and went out and brought in one wagon and cashed the other tow and a grate man a things all but what we could put in our Wagon

According to Eddy as recorded by Thornton:

On the afternoon ... they started back with Mr. Reed and Mr. Graves, for the wagons of the Messrs. Donner and Reed; and brought them up with horses and mules, on the evening ....One of Mr. Reed’s wagons was brought to camp; and two, with all they contained, were buried in the plain.

Unfortunately, Thornton had elaborated on statements that the wagons were cached

and wrote that they were buried.

Virginia Reed continued this elaboration in her letters to C.F. McGlashan, and in her 1891 Century magazine article:

We realized that our wagons must be abandoned. The company kindly let us have two yoke of oxen, so with our ox and cow yoked together we could bring one wagon, but, alas! not the one which seemed so much like a home to us, and in which grandma had died. Some of the company went back with papa and assisted him in cacheing everything that could not be packed in one wagon. A cache was made by digging a hole in the ground, in which a box or the bed of a wagon was placed. Articles to be buried were packed into this box, covered with boards, and the earth thrown in upn them, and thus they were hidden from sight.

Thus were created two Donner Party myths. First, the myth that the wagons were buried. It should have always been doubted that the party members, after crossing the desert, would have had the time, the strength or the inclination to dig holes in the desert. Besides, later travelers reported the wagons standing on the salt plain.

In the fall of 1847, a detachment of the Mormon Batallion under Captain James Brown crossed the desert, and, according to diarist Abner Blackburn, Stopt at some abandoned wagons we were cold pulled the wagons together set them an fire and had a good warm ....

We passed during the night 4 wagons and one cart, with innumerable articles of clothing, tools chests trunks books & yokes, chains, & some half dozen dead oxen. Encamped on the wet sand & had for wood part of an ox yoke and the remains of a barrel & part of an old wagon bed.

Grantsville, Utah, ranchers Dan Hunt, Quince Knowlton and Steven Worthington passed the sites in about 1875, and reported that the wagons had fallen down and were collecting mounds of sand.

After the publication of McGlashan’s articles and book in 1878-80, and Virginia Reed’s articles in 1891, these observations were ignored and the myth took hold. It was somewhat reinforced by Charles Kelly’s expeditions to the sites beginning in 1929. Kelly found an empty wagon box under a sand dune, which led some people to conclude that the wagon had been buried, even though Kelly himself wrote that you could not dig a hole in the mudflats deeper than 8 inches because it would fill with salt water. The 1986 Hill Air Force Base expedition, reported by Hawkins and Madsen, excavated five sites, and found no evidence of burial.

The second myth was that Reed’s huge Pioneer Palace Car

was abandoned in the Salt Desert. In 1930,Kelly wrote of finding

four wheels, lying close together, the hubs only showing above the sand. These hubs, from their enormous size together with the heavy oak wheels which we soon exposed to view, indicated a wagon of unusual proportions, being larger and heavier than any others we found there. ... Continuing eastward, we shortly encountered the remains of another wagon, not as large, ....

But Reed himself wrote in 1871, he was able to bring in the wagon that had been used for my family.

Reed’s memory was proven correct in 1986 when the Hill Air Force Base archaeologists found wagon tracks in the desert playa, and measured all the tracks at about 58” to 59” wide, except for one set of 86” wide tracks. The wider tracks do not end in a pile of wagon remnants, but pass by such a pile, confirming that Reed drove the Pioneer Palace Car

past the abandoned wagons to salvage what provisions he could.

Remains of Reed Wagon, Photographed by Charles Kelly, 1929

Remains of Donner and Keseburg Wagons, Photographed by Charles Kelly, 1929

Sadly, we will never be able to learn anything more from these sites. Most of the second half of the the dry drive, about 25 miles from Interstate 80 to the Silver Island Mountains, is now submerged under the Newfoundland Evaporation Basin created in 1988 by the State of Utah’s West Desert Pumping Project. This project was designed to prevent the flooding of the developed areas around the Great Salt Lake caused by the periodic fluctuations in the lake level.

Fortunately, some of the artifacts recovered during the early expeditions are on display at the Donner-Reed Museum in Grantsville, Utah, and at the Donner Memorial State Park Museum in Truckee, California. Unfortunately, many other artifacts were recovered from the sites only to be lost years later.

Wagon Artifacts at Donner-Reed Museum, Grantsville, UT, photographed 1999

Monday, September 7, 1846

Mond 7 Cam in to Camp on the Night and the waggon Came in on Tuesday morng

Tuesday, September 8, 1846

Tudy 8 Still fixing and resting Cattle

According to John Breen, as told by Eliza Farnham in her 1856 book California In-doors and Out:

After we got across, we laid by one or two days to recruit; but, when we were ready to start, Mr. R.’s last yoke of cattle were missing; so, all hands turned out, and made a general search for six days, but we found no trace of them. In fact, it was impossible to find cattle on those plains, as the mirage, when the sun shone, would make every object the size of a man’s hat look as large as an ox, at the distance of a mile or more; so one could ramble all day from one of these delusions to another, till he became almost heart-broken from disappointment, and famished from thirst.

In all likelihood, Breen was wrong about searching for one yoke. The party probably was searching for the nine yokes lost by Reed’s teamsters during the dry drive on September 2.

Wednesday, September 9, 1846

Weds 9 Mr Graves Mr Pike & Mr Brin loaned 2 Yoke of Cattle to J F Reed with one Yoke he tried to bring his family waggon along

Reed’s diary entry again refers to the family waggon

contradicting Virginia’s 1891 memoir that the Pioneer Palace Car was buried in the Salt Desert.

Thirteen year old Virginia Reed wrote to her cousin Mary Keyes in a letter dated May 16, 1847: we head to devied our provisions out to them to get them to carie them We got three yoak with our oxe & cow so we on that way a while ....

Reed’s difficulty traveling was commented upon by John Breen, as recorded in Eliza Farnham’s 1856 book California, In-doors and Out: One man lost all his oxen but one yoke, and was, consequently, compelled to leave all his wagons but one, into which he put a large family and their provisions, which, of course, made traveling very tedious.

In his 1871 article in the Pacific Rural Press, Reed wrote:

I divided my provisions with those who were nearly out, and indeed some of them were in need. I had now to make arrangement for sufficient team to haul that one wagon; one of the company kindly loaned me a yoke of cattle, and with the ox and cow I had, made two yoke. We remained at this camp from first to last, if my memory is right, seven days.

Apparently, Reed did not remember, and did not refer to his diary entry, that more than one member of the Party lent oxen to him.

Virginia Reed wrote in her Century Magazine article in 1891:

Our provisions were divided among the company. Before leaving the desert camp, an inventory of provisions on hand was taken, and it was found that the supply was not sufficient to last us through to California, and as if to render the situation more terrible, a storm came on during the night and the hill-tops became white with snow.

Thursday, September 10, 1846

Thu 10 left Camp and proceeded up the lake bed 7

The Trail followed the faint wagon tracks left by the Bidwell-Bartleson Party in 1841, when they became the first party to bring wagons across the Salt Desert, north of the Great Salt Lake. The Trail went southwesterly around the base of Pilot Peak and over a low pass now called Bidwell Pass, named in honor of the first party to bring wagons through Utah in 1841. The Donner Party probably camped along Pilot Creek towards present Silver Zone Pass, northwest of Wendover, Nevada.

As remembered by John Breen, 14 at the time, and told to Eliza Farnham shortly after his arrival in California, and published in Farnham’s California In-doors and Out in 1856:

... on the morning of their leaving the long encampment at the desert, there appeared a considerable fall of snow on the neighboring hills. The apprehension of delay from this cause, and of scarcity, made the mothers tremble.

Bidwell Pass with Crossroads (OCTA Utah) Trail Exhibit, photographed 1999

Trail from Bidwell Pass past Pilot Creek, photographed 1999

Friday, September 11, 1846

Frid 11 left the Onfortunate lake and mad in the night and day about 23 Encamped in Vally wher the is fine grass & water

Here was another day and night dry drive, over Silver Zone Pass. In another example of Reed updating his diary after the fact, he records the arrival at the next camp under the date of the 11th, when actually they traveled the entire day.

Trail to Silver Zone Pass with Trails West Trail Marker, photographed 1999

Saturday, September 12, 1846

Sat 12

Although Reed wrote of the campsite in his diary entry of the 11th, the actual arrival was on the 12th, after driving all night. The camp was at present Big Springs Ranch, in a valley on the east side of the Pequop Mountains, south of Oasis, Nevada.

T.H. Jefferson on his 1846 map called this camp Relief Springs,

the location of Chiles Cache.

Chiles had guided the Bidwell-Bartleson Party in 1841 from the Bear River around the north shore of the Great Salt Lake to this campsite where they abandoned their wagons and continued by pack train to California.

According to Eddy, as recorded by Thornton,

they arrived at water and grass, some of their cattle having perished, and the teams which survived being in a very enfeebled condition. Here the most of the little property of which Mr. Reed still had, was buried, or cached, together with that of others. .... Here, Mr. Eddy, proposed putting his team to Mr. Reed’s wagon, and letting Mr. Pike have his wagon, so that the three families could be taken on. This was done.

Although not mentioned by Reed in his diary, on this day, according to George McKinstry in his letter to the California Star, published February 13, 1847:

After crossing the long drive of 75 miles without water or grass, and suffering much from loss of oxen, they sent on two men (Mrs. Stanton and McCutcher.) They left the company recruiting on the second long drive of 35 miles, ....

McKinstry probably obtained this account from John Sutter, who spoke to Stanton and McCutcheon.

James Reed wrote in his 1871 article in the Pacific Rural Press that

it became known that some families had not enough of provisions remaining to supply them through; as a member of the company, I advised them to make an estimate of provisions on hand and what amount each family would need to take them through. After receiving the estimate of each family, on paper, I then suggested that if two gentlemen of the company would volunteer to go in advance to Captain Sutters (near Sacramento), in California, I would write a letter to him for the whole amount of provisions that were wanted, and also stating that I would become personally responsible to him for the amount. I suggested that from the generous nature of Captain Sutter he would send them. Mr. McCutchen came forward and proposed that if they would take care of his family he would go. This the company agreed to. Mr. Stanton, a single man, volunteered, if they would furnish him a horse. Mr. McCutchen, having a horse and a mule, generously gave the mule. Taking their blankets and provisions they started for California.

The content of Reed’s letter is not known, but Sutter did hold Reed alone to be responsible for the amount. Among the papers found in the Miller-Reed Diary was this letter:

James F. Reed Esqre

My Dear Sir:

I have forgotten to ask you for a copy of the list of those who have to pay for my mules, etc. which you has been so kind to make out; I wish you would have the goodness to send me a copy by the first opportunity, and you will oblige me very much.

I remain respectfully

Your most Obedient Servant

J.A. Sutter

Virginia Reed wrote in her Century Magazine article in 1891: Some one must go on to Sutter’s Fort after provisions. A call was made for volunteers. C.T. Stanton and Wm. McCutchen bravely offered their services and started on bearing letters from the company to Captain Sutter asking for relief.

Some accounts have Stanton and McCutchen leaving while the party recruited from the dry drive across the Salt Desert, such as John Breen’s account published in 1856 in Eliza Farnham’s California In-doors and Out: While we laid here, two men were sent on, on horseback, to California, to get provisions, and return to meet us on the Humboldt.

Relief Springs, on Big Springs Ranch (private property) south of Oasis, NV, photographed 1999

Sunday, September 13, 1846

Sund 13 south in the Vally to fine Sping or Bason of water and grass--sufficient for Teams made this day 13

[The basin is now known as Flowery Lake.]

Monday, September 14, 1846

Mond 14 left the Bason Camp or Mad Woman Camp as all the women in Camp ware mad with anger and mad this dy to the Two mound springs 14

[The route crossed the present Pequop Mountains at Jasper Pass to Mound Springs north of Spruce Mountain.]

There must have been something strange about this campsite, as Edwin Bryant also reported high emotions. In his diary entry of August 7, Bryant wrote:

A disagreeable altercation took place between two members of our party about a very trivial matter in dispute, but threatening fatal consequences. Under the excitement of angry emotions, rifles were leveled and the clock of the locks, ... was heard. ... It was truly a startling spectacle, to witness two men, in this remote desert, surrounded by innumerable dangers, ... so excited by their passions as to seek each other’s destruction.

Tuesday, September 15, 1846

Tus 15 left the 2 mound Spings and Crossed the Mountain as usual and Camped in the West Side of a Valley and Made this day about 14

[The route crossed the present Spruce Mountain Ridge to Warm Spring in Clover Valley, near Snow Water Lake off of US Highway 93, about 20 miles south of Wells, Nevada.]

From this valley, the Donner Party could have traveled two days north along the east side of the East Humboldt Range, over relatively easy country (the route of present US Highway 93) directly to the wells at the head of the Humboldt River (outside present Wells, Nevada). However Hastings, like the Bartleson Party five years earlier, was unaware of this route. Instead, Hastings led the Harlan-Young wagons south to find a pass around the mountains. The Donner Party had no choice but to follow.

Ruby Mountains, photographed 1999

Wednesday, September 16, 1846

Wed 16 left Camp Early this mornig Crossed flat Mounten or Hills and encamped on the east side of a Ruged Mountain plenty of grass & water 18 here Geo Donner lost little gray & his Cream Col mare Margret

[The route crossed the East Humboldt Range along the route of present Nevada Highway 229. The camp was in the north end of Ruby Valley, below the high point of the Ruby Mountains, Ruby Dome (11,387’).]

To the north of this camp was a steep, narrow pass through the Ruby Mountains, now called Secret Pass. Hastings had crossed this pass on his pack-train journey east from California the previous Spring. But the pass was too difficult for wagons, and Hastings had led the Harlan-Young wagons south in Ruby Valley towards a lower pass. The Donners followed.

Secret Pass, photographed 1999

Steep Canyon in Secret Pass, photographed 1999

Thursday, September 17, 1846

Thu 17 made this day South in the Mineral Vally about 16

[The camp was near the present Ruby Valley Indian Reservation.]

Friday, September 18, 1846

Frid 18 this day lay in camp

Saturday, September 19, 1846

Sat 19 this day mad in Minral Vally 16 and encamped at a large Spring Breaking out from the and part of a large Rock Stream lage enough to turn one pr Stone passed in the evening about 10 Spring Branches Springs Rising about 300 Yds above where we Crossed

[The camp was on present Cave Creek, at the Headquarters of the Ruby Lake National Wildlife Refuge.]

Cave Creek, photographed 1999

Sunday, September 20, 1846

Son 20 this day made 10 up the Mineral Vally passed last evening and this day 42 Beautiful Springs of fresh water

Reed added in the margin: 384 miles from Bridger

[The springs are in the present Ruby Lake Wildlife Refuge along the eastern base of the Ruby Mountains. The camp was at the east entrance to Overland Pass.]

During their journey south through the Ruby Valley, as noted by Thornton, They proceeded down this valley three days, making about fifty miles of travel.

Monday, September 21, 1846

Mond 21 Made 4 miles in Mineral Valley due south turned to the west 4 Miles through a flatt in the mounton thence W N W, 7 miles in another vally and encamped on a Smal but handsome littl Branch or Creek making in all 13 miles

[The trail crossed the present Ruby Mountains over the broad, relatively low (6,789’) Overland Pass to Huntington Creek. Overland Pass later became the route of the Pony Express.]

Overland Pass, photographed 1999

Tuesday, September 22, 1846

Tus 22 Made this day nearly due North in Sinking Creek Valy about ten miles owing to water. 10

[Reed’s apt name for Huntington Creek, which flows underground for about 15 miles. This camp probably was at the point the creek disappeared underground.]

Trail in Huntington Valley south of Jiggs, NV, photographed 1999

Wednesday, September 23, 1846

Wed 23 Made this day owing to water about Twelve 12 miles Still in Sinking Creek Valley-

[This camp was south of present Jiggs, Nevada, at the western entrance to Harrison Pass.]

Thursday, September 24, 1846

Thu 24 this day North west we mad down Sinking Creek valley about 10 and encamped at the foot of a Red earth hill good grass and water wood plenty in the Vallies Such as sage greace wood & ceder &C--

[The Camp was near the entrance to the canyon of the South Fork of the Humboldt River.]

South Fork of the Humboldt River, photographed 1999

Friday, September 25, 1846

Frid 25 September This day we made about Sixteen miles 16 for Six miles a very rough Cannon a perfect Snake trail encamped in the Cannon about 2 miles from its mout

[This camp was in the canyon of the South Fork of the Humboldt, southwest of present Elko, Nevada.]

Saturday, September 26, 1846

Sat 26 this day made 2 miles in the Cannon and traveled to the Junction of Marys River in all about 8

[The camp was along the Humboldt River near present Hunter Siding, NV.]

Junction with the South Fork of the Humboldt River at Hunter Siding, NV, photographed 1999

Here, the Donner Party completed the crossing of Hasting’s Cut-off, and rejoined the California Trail at the present Hunters Siding. On July 31, 1846, Reed had written to his brother-in-law from Bridger’s Fort:

The new road, or Hastings’ Cut-off, leaves the Fort Hall road here, and is said to be a saving of 350 or 400 miles ... and a better route. The rest of the Californians went the long route--feeling afraid of Hasting’s Cut-off.

Which really was the long route?

On July 20, the Donner Party had made their initial decision to take the Cut-off. At the Little Sandy River in Wyoming, they passed Greenwood’s cut-off to the Bear River, the most direct route to Fort Hall. Eleven days later, they passed up their last chance to take the old Fort Hall road from Bridger’s Fort. Sixty-eight days after leaving the Little Sandy, they completed the Hastings Cut-off. And what of those who went the long route?

Four days ahead of the Donner Party at the Little Sandy, the Cooper-Gregg Party took the Fort Hall road. According to Nicholas Cariger’s diary, they reached the Little Sandy on July 16, and the South Fork of Marys River thirty-seven days later on August 22. By comparison, the first wagon party across the Trail in 1846, the Craig and Stanley Party, took thirty-five days (from July 1 to August 5) according to diarist William E. Taylor.

Those who followed Hastings and Hudspeth down the Weber River Canyon and across the Salt Desert were faster than the Donner Party, but still slower than the Fort Hall parties. Map maker T.H. Jefferson reached the Little Sandy two days ahead of the Donner Party on July 18, and arrived at Mary’s River fifty-two days later on September 8. James Mathers, who was at the Little Sandy three days sooner on July 15, arrived at Mary’s River with Jefferson.

At its best, the Hastings Cut-off was fifteen days slower than the Fort Hall road. The Donners were sixteen days slower than that, or a full month slower than the Fort Hall parties.

Although Hastings had not found a viable short-cut in 1846, his geographic sense was ultimately proven correct. Along its entire 380 mile distance from Fort Bridger, Wyoming, to the Humboldt River below Elko, Nevada, the Cut-off is never more than 50 miles from the route of Interstate 80, the fastest and most direct route across the central US today. Had Hastings not rounded the Ruby Mountains, but instead discovered the pass on the east side of the Humboldt Range direct to the Wells (present Wells, Nevada), his cut-off would be within 20 miles of Interstate 80 its entire distance.

Sunday, September 27, 1846

Marys River, Son 27 Came through a Short Cannon and encamped above the first Creek (after the Cannon) on Marys River

[This camp was probably on present Susie Creek, also called Moleen Canyon, below Carlin, Nevada.]

Monday, September 28, 1846

Mond 28 this day after leaving Camp about 4 miles J F Reed found Hot Springs one as hot as boiling water left the River Crossed over the Mounta to the west Side of a Cann, and encamp in Vally 12

[The hot springs are at present Carlin, Nevada. The Trail left the north bank of the Humboldt and crossed present Emigrant Pass, to the camp in the valley between Emigrant Pass and Twin Summit.]

Tuesday, September 29, 1846

Tus 29 This day 11 O.Clock left Camp and went about 8 miles to the river again 2 grave had 2 oxen taken by 2 Indians that Cam with us all day

[The Trail returned to the Humboldt River at Gravelly Ford, near present Beowawe, Nevada.]

William C. Graves, in his memoirs in the Russian River Flag, April 26 1877, wrote: Then we had no more trouble till we got to Gravelly Ford, on the Humboldt, where the Indians stole two of father’s oxen ...

Thornton’s account, based on Eddy:

About 11 o’clock, an Indian, who spoke a little English, came to them, .... About 4 o’clock, P.M., another came to them, who also spoke a little English. He frequently used the wordsjee,who,andhuoy;thereby showing that he had been with previous emigrants. They traveled all that day, and at dark encamped at a spring about half way down the side of a mountain. A fire broke out in the grass, soon after the camp fires had been kindled, which would have consumed three of the wagons, but for the assistance of these two Indians. The Indians were fed, and after the evening meal they lay down by one of the fires, but rose in the night, stealing a fine shirt and a yoke of oxen from Mr. Graves.

Wednesday, September 30, 1846

Wed 30 left Camp about 10 oclock and made this day 12 Miles down the River

[The camp was near present Dunphy, Nevada.]