July, 1846

The emigrants who would later form the Donner Party traveled from the Platte River near Laramie Peak, in what is now eastern Wyoming to Bridger’s Fort in what is now southwestern Wyoming.

The dated entries below are from the diary of Hiram Miller and James F. Reed. The Diary is controversial to some historians. The existence of the diary was not known until the estate of Martha (Patty) Reed donated it to Sutter’s Fort Historical Museum in 1945. Apparently neither Virginia nor Patty revealed the diary to McGlashan. Virginia apparently did not use it as a source for her Century Magazine article in 1891. Some of the entries appear to have been written after the events, which led both Stewart and King to question it. King went so far as to suggest that some entries may have been written after Reed arrived in California, which seems unlikely.

Wednesday, July 1, 1846

July 1 1846 1 and from their we traveled a Bout 15 miles and Camped near a Creek their is a fine Spring and timber plenty we are now in the red mouns devils Brick kilns

[This camp was on present La Bonte Creek.]

Trail Through the Red Hills, as drawn by James Wilkins in 1849

Thursday, July 2, 1846

2 and from their we traveled a Bowt 15 miles and Camped on a Creek their is plenty of water and timber

[This was the last entry by Hiram Miller.]

Bryant records Miller’s exodus from the Reed-Donner Party. On June 27, at Fort Bernard, Bryant had traded his wagon and oxen for mules and packs, and spent the next several days preparing:

Mr. Kirkendall, whom I expected would accompany us, having changed his destination from California to Oregon, ... we were compelled to strengthen our party by adding to it some other person in his place. ... I rode back some five or six miles, where I met Governor Bogg’s company, and prevailed upon Mr. Hiram Miller, a member of it, to join us.

Friday, July 3, 1846

3 we made this day 18 Miles and Camped on Beaver Creek here is a natural Bridge 1 1/2 miles above camp

[This is the first entry by James Reed. The natural bridge is in La Prele Creek in Ayers Park, west of Douglas, Wyoming.]

The Wyoming Pioneer Memorial Museum in Douglas, located on the Douglas County Fairgrounds, contains excellent exhibits on the Trail, including Indians, life on the Trail, clothing and maps.

Saturday, July 4, and Sunday, July 5, 1846

4 we Celebrated the glorious 4th on the Camp and remained here to the morning of the 6th

Virginia Reed, 12 years old, described the celebration in a letter she wrote on July 12:

We celebrated the 4 of July on plat at Bever crick, several of the gentemen in Springfield gave paw a botel of liker and said it shouden be opend till the 4 day of July and paw was to look to the east and drink it and they was to look to the West and drink it at 12 o clock paw treted the company and we all had some lemminade,

Bryant described the celebration, which was considerably enhanced by James Reed:

Gov. Bogg’s emigrant company having arrived and encamped just above us last night, it was resolved, out of respect to the the birthday of our National Independence, to celebrate it in the usual manner, so far as we had the ability so to do. Mr. J. H. Reed had preserved some wines and liquors especially for this occasion.... At nine o’clock A.M., our united parties convened in a grove near the emigrant encampment. A salute of small arms was discharged. [Bryant refers to James F. Reed as "J. H. Reed" as when he described Sarah Keyes’ death on May 29.]

Charles Stanton described the celebration in his letter of the July 5:

Yesterday, as I said before, we celebrated the 4th of July. The breaking one or two bottles of good liquor, which had been hid to prevent a few old tapsters from stealing, (so thirsty do they become on this route for liquor, of any kind, that the stealing of it is thought no crime), a speech or oration from Col. Russell, a few songs from Mr. Bryant, and several other gentlemen, with music, consisting of a fiddle, flute, a dog drum--the dog from which the skin was taken was killed, and the drum made the night previous--with the discharge of all the guns of the camp, at the end of speech, song and toast, created one of the most pleasurable excitements we have had on the road.

Meanwhile, back on the Trail, the Graves family, traveling with the Smith Company, celebrated the Fourth at Fort Laramie, as recounted by William Graves in his 1877 article in the Russian River Flag: We got to Fort Laramie on the third of July and stayed there until the fifth, celebrating the fourth by giving the Indians a few presents.

Monday, July 6, 1846

6 we left Camp much rested and our Oxen mouved off in fine Style, and went 16 miles and encamped on the Bank of Creek about 1/2 a Mile from the North fork of the Platt which Stream we struck about 6 miles from Camp, where there is a fine Coal Bank

[The coal is located along Deer Creek, near present Glenrock, Wyoming.]

Charles Stanton recorded the voyage in a letter he wrote to his brother on July 12:

On the morning of July 6th, after our two days’ rest, we got underway and traveled twenty miles to Deer Creek. Laramie’s Peak was visible almost the whole day, off to the south east. About noon we came to the north fork of the Platte, after having been absent from it over a week. Where we struck the river, there is a fine bed of stone coal; but the great Platte, on which we had traveled so long and far, how it had dwindled down, or rather up, to a small stream. The water was clear, but I did not like it as well as I did when mixed with sand and loam when we first struck the river.

In her 1891 memoirs, Virginia Reed described the journey through Sioux country:

On the sixth of July we were again on the march. The Sioux were several days in passing our caravan, not on account of the length of our train, but because there were so many Sioux. Owing to the fact that our wagons were strung so far apart, they could have massacred our whole party without much loss to themselves. Some of our company became alarmed, and the rifles were cleaned out and loaded, to let the warriors see that we were prepared to fight; but the Sioux never showed any inclination to disturb us. ...their desire to possess my pony was so strong that at last I had to ride in the wagon, and let one of the drivers take charge of Billy. This I did not like, and in order to see how far back the line of warriors extended, I picked up a large field-glass which hung on a rack, and as I pulled it out with a click, the warriors jumped back, wheeled their ponies and scattered. This pleased me greatly, and I told my mother I could fight the whole Sioux tribe with a spyglass, ....

Tuesday, July 7, 1846

7 left Camp in good order and mouved up Platt 16 and encamped on the Bank in Beautiful grove of Cotton wood here we killed Buffalo

Wednesday, July 8, 1846

Wed 8 went up Platt this day Crossed over and encamped opposit the upper Crossing 12 be Certain to Come up on the South sid & Cross- the road & ford is desidedly the best

[The upper crossing is about 4 miles west of present Casper, Wyoming. The more difficult lower crossing is in eastern Casper.]

Charles Stanton recorded the voyage of the 7th and 8th in a letter to his brother of July 12:

We traveled all the next day up the Platte, and camped near a small grove on the banks of the river. On Wednesday we crossed the Platte about noon, and drove on six miles. The buffalo and other game are becoming plentiful. Every day one or more is killed, and we are again luxuriating on fresh meat. I think there is no beef in the world equal to a fine buffalo cow--such a flavor, so rich, so juicy, it makes the mouth water to think of it.

Casper is home to the National Historic Trails Interpretive Center which has exhibits about the pioneers who traveled the California, Oregon and Pony Express Trails.

Thursday, July 9, 1846

Thur 9 left the Platt and encamped at the Spring in the bottom land of a dry Branch fine water and Plenty of it 5 Buffalos killed 12

Charles Stanton recorded the days journey in his letter of July 12:

On Thursday morning we left the Platte and the long range of black hills on our left, and struck off towards the Sweet Water. At noon, Col. Boon came up full of excitement, stating that he had been out with some others, and had killed eight buffaloes, among which were several fat cows and calves, and requested all who wanted buffalo meat to get what they wanted. ... In the afternoon, we drove a few miles and encamped by a fine spring.

Friday, July 10, 1846

Fri 10 made this day 14 and encamped at the Willo Springs good water but little grass 3 Buffaloes Killed the Main Spring 1 1/2 Miles above

Charles Stanton recorded an act of bravado by James Reed’s during the days’ journey:

The next day we drove 14 miles to Willow Sping. At noon we heard a great firing, and shortly after young Boggs came in and said they had killed one or two buffalo. Mr. Reid also shortly after came driving a fine buffalo bull, which he had slightly wounded, as he would an ox, up to the wagons.

Saturday, July 11, 1846

Sat 11 Made this day 20 Miles to Independence Rock Camped below the Rock good water 1/2 way

Independence Rock was named by early parties who had reached the rock around Independence Day. Most later parties tried to reach the rock by Independence Day, but the Reeds and Donners were a week late. You can see the Rock, and read the names of the many emigrants and 49’ers who carved their names in the rock, at Independence Rock State Historical Park on Highway 220 approximately 35 miles west of Casper, Wyoming.

Charles Stanton described the days’ journey to Independence Rock: The next day, Saturday, we started early, having twenty miles to go. The road was very sandy, and we had to travel very slow. It was just night when we reached the Sweet Water.

The Sweetwater River, from Independence Rock

(c) National Geographic Magazine

Sunday, July 12, 1846

Sun 12 Lay by this day

On this day, Virginia Reed, 12 years old, wrote a letter to her cousin Mary C. Keyes:

We diden see no Indians from the time we lefe the cow village till we come to fort Laramy the Caw Indians are going to war with the crows we have to pass throw ther Fiting grond, the Soux Indians are the pretest drest Indians there is, paw goes bufalo hunting most every day and kills 2 or 3 buffalo every day paw shot an elk some of our company saw a grisly bear We hve the thermometer 102--average for the last 6 days ... We have hard from uncle Cad severl times he went to california and now is gone to oregon he is well

Virginia’s reference to the cow

village is the Kaw, or Kansas village on the Kansas River. At Fort Laramie it was not the Kaw, but the Souix, who were going to war with the Crow. Virginia’s comment that they had heard from her uncle Robert Cadden Keyes in Oregon is interesting because such knowledge did not appear to affect James Reed’s decision to continue to California.

On this day, Charles Stanton wrote a letter to his brother Sidney, described the country:

The whole region of country from Fort Laramie to this place is almost entirely barren. There is no grass except in the valleys, which in some few places only, is found luxuriant. One seems at a loss how to account how the buffalo can live on the hills over which they range ... Over the whole region the wild sage or artemisia grows in abundance. ... The sage is not like the sage of the garden. It has more the smell of lavender, and an Englishman ofour messsticks to it that it is nothing else. ... The first week after leaving the Fort, we experienced, though in midsummer, the cool mountain breezes, being necessary at night to bundle ourselves up in our overcoats, and oftentimes through the whole day. The past week, however, it has been different. It has been insufferably hot both day and night--thermometer ranging from 95 to 100 degrees. ... the Oregon party ... left two or three families with us. The influence of these, with the information derived from the Oregon and California travelers, ... have cast a shade on all those that were thither bound, and induced many to change their minds. Today a division of our company took place, Governor Boggs, Colonel Boon, and several other familiesslidingout, leaving us but a small company of eighteen wagons.

The Englishman

was probably John Denton, traveling with the Donners. With the departure of the Oregon-bound parties, the remaining eighteen wagons formed the Donner Party. With the exception of the stragglers picked up later, and the Graves family, it is likely that all the other families were now traveling with the Reeds and Donners.

Monday, July 13, 1846

Mo 13. left the Rock after Reading many Names and Made 20 Encaped at the Sand Ridge

Charles Stanton wrote of Independence Rock in his letter of July 19 to his brother Sidney:

A drive of five miles brought us to Independence Rock, in the appearance of which we were all disappointed, as we expected to find a rock so high that you could hardly see its top; but instead of that, in seen from the distance, it looked tame and uninteresting. It is about 600 yards long, and about 140 feet high, of an oval shape--one solid mass of granite, rising perpendicularly fro the green bottom lands of the Sweet Water.--Its sides, to the height of 80 feet, are covered with names of travelers who have passed by. There is an indentation about half way up it top, where there is a single pine tree growing. Hastings, in his trip to California in 1842, in attempting to climb the rock to this tree, was taken prisoner by Indians.

The reference to Hastings suggests that someone in the party, perhaps the Breens, had a copy of Hastings Guide. It is easy to see why the Party was disappointed with Independence Rock. Compare Wilkins’ drawing with a photograph of the Rock, below.

Independence Rock drawn by James Wilkins, 1849

Photo of Independence Rock by William Jackson, 1870

Stanton described the day’s journey:

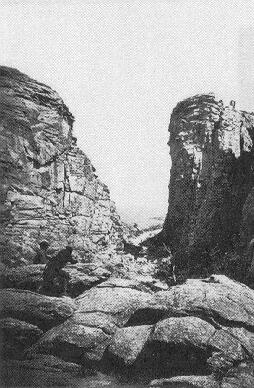

In about eight miles further, we came to theDevil’s Gate,where wenooned,and the most of our party walked down to take a look at it. The Sweet Water at this place makes a gap through a rock mountain, which on either side rises 400 feet from the water. The rock is of granite, single pieces of which, as large as an ordinary house, are found in this place. We drove on till sun down, and caught up with Bogg’s company, which had left us the day before, and encamped. No scenery in our whole route has been more delightful than that seen in this day’s drive. The valley of the Sweet Water is about five miles wide. On one right was a long line of rock hills or mountains, from three to five hundred feet in height, rising directly from the smooth level of rich meadow land. Nothing could present a greater contrast with the sterile granite mountains, than this.

Devil’s Gate, photographed by William Jackson, 1870

Although Devil’s Gate is on private land, you can see it from an interpretive site on Wyoming Hwy. 220, about five miles west of Independence Rock.

Tuesday, July 14, 1846

Tus 14 left our encampmt and Crossed the Sand Ridge to the Narrows of sweet water a sandy Road 20 Bad Bad Road

Stanton describes the Narrows and the bad road:

In the morning we drove on, and in a short time entered theNarrows,a place so called, where the river and the road runs through steep rock mountains, which rise three or four hundred feet high on either side. This was a wild and romantic place. On arriving at the end of this gap, the road struck upon a rather elevated sandy ridge, and we drove til sundown without reaching the river, and were compelled to camp on a small stream which furnished scarcely water for the cattle. Here Bogg’s company came up and stayed with us; but they fully repaid our hospitality, for in the morning they stole the march on us--rolling outfirst--leaving us to get along as best we might. This movement chagrined many of our party, as we by courtesy were entitled to the lead.

Wednesday, July 15, 1846

Wed 15 this day Crossed a Ridges to Sweetwater and made 16. Encamped at the foot of the Mountain

Stanton described the view of the mountains:

We had from this place the first view ofthe snow clad mountains,lying off to the northwest. It was the Wind river chain, and many of the peaks were covered with snow. It was now midsummer--we had been traveling for the past ten days under a broiling sun, and it was strange thus suddenly to see this winter appearance on the distant hills.

The Valley of the Sweetwater, drawn by James Wilkins, 1849

Thursday, July 16, 1846

Thur 16 Crossed the Mountain 14

The following words were crossed out in Reed’s diary: here Some of our Cattle got poisoned from drinking bad water there are about 1 Mile from Our encampmt 3 or 4 hot Springs, the water Sinks near the road where the encampmt is usually made go if possible 3 miles further to the Crossing

On this day, up ahead on the Trail at Bridger’s Fort, Lansford Hastings was greeting the emigrants. As reported by an unknown emigrant in a letter dated July 23, and carried by Joseph Walker until mailed to the Missouri Republican, the writer reported:

Col. Russell and his party, by hard traveling, reached Fort Bridger two or three days before the others, ... At that place they were met by Mr. Hastings, from California, who came out to conduct them in by the new route, by the foot of Salt Lake, discovered by capt. Fremont, which is said to be two hundred miles nearer than the old one, by Fort Hall. The distance to California was said to be six hundred and fifty miles, through a fine farming country, with plenty of grass for the cattle. Companies of from one to a dozen wagons, ... are continually arriving, and several have already started on, with Hastings at their head, who would conduct them to near where the road joins the old route, ...

Friday, July 17, 1846

Frid 17 Came from the Mountain 16 to last Crossing of Sweet water

[Actually, this was not the last crossing of the Sweetwater, so it is possible that Reed wrote this entry for the wrong date.]

Charles Stanton wrote a letter two days later, in which he described the Party’s excitement at leaving the Sweetwater to cross the Continental Divide.

One or two miles brought us to the high hill ... up which we wound our way, and were two or three hours in reaching its summit. Many supposed, with myself among the number, that this rocky ridge was theculminating point,and that we were now on the waters that flowed to the Pacific. ... To the west, as well as to the east, the view was unobstructed and every thing seemed to indicate this to be the South Pass, according to the description given of it by Fremont; but we were mistaken. We drove on till night, when we came to a pure stream, with a swift current, ... as its general current was east, and we all had no doubt but that we were again on the banks of the Sweet Water.

View of South Pass, drawn by James Wilkins in 1849, show the Divide is very gentle

Plume Rock near South Pass

With the last crossing of the Sweetwater, the Trail took a course not followed by modern highways. Up to this point, you can follow the North Platte along US 26 (from Ash Hollow, Nebraska to Guernsey, Wyoming), Interstate 25 (to Casper, Wyoming), Wyoming Hwy 220 (to Independence Rock), and US 287 to the last crossing of the Sweetwater in the Antelope Hills. Hikers and packers can experience the excitement of the approach to South Pass, where the Trail meets up with Wyoming Hwy. 28. Or, from the South Pass interpretive site on Hwy 28 you can drive east along the old Trail towards South Pass. From there you can follow the Trail (now an old dirt road) west to Pacific Springs.

Saturday, July 18, 1846

Sater 18 this day nooned on the Sumit of the pass. 6 miles from our encampmt and 2 miles below on the west side is the green Spring which You Can See from the Sumit and about 6 miles from this Sping is dry Sandy which You will avoid as Several Cattle got poisoned by drink the water in the pools.

On this day, the Party crossed the Continental Divide at South Pass. Reed’s green Spring

is Pacific Spring. Charles Stanton described the excitement of reaching this milestone:

Yesterday at noon we arrived at theculminating point,or dividing ridge between the Atlantic and Pacific. This evening we are encamped on the Little Sandy, one of the forks of the Green river, which is a tributary of the great Colorado, which flows into the gulf of California. Thus the great day-dreams of my youth and of my riper years is accomplished. I have seen the Rocky mountains--have crossed the Rubicon, an am now on the waters that flow to the Pacific! It seems as if I had left the old world behind, and that a new one is dawning upon me. In every step thus far there has been something new, something to attract.--Should the remainder of my journey be as interesting, I shall be abundantly repaid for the toils and hardships of this arduous trip.

Pacific Spring, drawn by James Wilkins, 1849

The next day Stanton described the events of the 18th, which foreshadowed many of the decisions made later in the journey:

In the morning, Saturday, we got an early start, and drove about ten or twenty miles andnooned,without finding water for our cattle. This place was on a ridge. ... After our usual delay, we were again on the road, and after a few hours drive, came to a fine spring, with the grass looking green about it. The managers of our company finding it rather boggy, thought the cattle would get mired should they attempt to feed upon the rich herbage, and concluded to go on till they found better grass, before they stopped for the night. We therefore drove on till nearly sun-down, but came to no more water or grass. We presently came to a deep gully, where there was a little water, but no grass and were going by without paying it a passing notice, when Mr. R., who had been sent on a head to look out for a camping place, was seen returning at full gallop. He soon came up and told us that we must go back to the gully and stay, as bad as it was. It was after dark that night before we got our suppers. Mr. D. who had been out with R. had not returned, and we all concluded that he must be lost. Guns were fired and beacons placed on the surrounding hills. At 12 o’clock, he made his appearance. [Mr. R. was likely Reed, and Mr. D. was likely one of the Donner brothers.]

Up ahead on the Trail, Bryant set out after several day’s rest at Bridger’s Fort. The day before, he spoke to Joesph Walker, who spoke discouragingly of the new route via the south end of the Salt Lake.

On this day, the 18th, Bryant and his party

determined this morning, to take the new route, via the south end of the great Salt Lake. Mr. Hudspeth--who with a small party, on Monday, will start in advance of the emigrant companies which intend traveling by this route, for the purpose of making some further explorations--has volunteered to guide us as far as the Salt Plain, a day’s journey west of the Lake. Although much was my own determination, I wrote several letters to my friends among the emigrant parties to the rear, advising them not to take this route, but to keep on the old trail, via Fort Hall. Our situation was different from theirs. We were mounted on mules, had no families, and could afford to hazard experiments, and make explorations. They could not.

Sunday, July 19, 1846

Son 19 Made this day 10 Miles to little Sandy here Geo. Donner & J. Donner lost 2 oxen &J F Reed lost old Balley 5 miles west of this place from being poisond at dry Sandy. Gurge also got poison there.

James Reed wrote in a letter dated July 31, 1846 from Fort Bridger:

We have arrived here safe with the loss of two yoke of my best oxen. They were poisoned by drinking water in a little creek called Dry Sandy, situated between the Green Spring in the Pass of the Mountains, and Little Sandy. The water was standing in puddles.--Jacob Donner also lost two yoke, and George Donner a yoke and half, all supposed from the same cause.

Virginia Reed, 12 at the time, mentioned the loss of cattle in a letter written

to her cousin Mary Keyes on May 16, 1847: My dear Cousin I am going to Write to you about our trubels getting to California; We had good luck til we come to big Sandy thare we lost our best yoak of oxen

On this day, Stanton wrote a letter to his brother Sidney, in which he describes the Party’s discovery that they had indeed crossed the Continental Divide.

The next day, Sunday, we travelled on till noon, but found no wood or water; and it was not till the middle of the afternoon, that we reached a small stream, where we encamped. This stream was of a swift current and sandy color, and its general course was westward. This surprised the most of us, as now they were willing to acknowledge that they had crossed the dividing ridge without knowing it. But it was true. The place where we hadnoonedthe day before, with the table mound on our right and the little mound on our left, was theculminating pointbetween the Atlantic and Pacific; and the spring around which the grass grew so green was the green spring--the first water that flows westward.

South Pass is very gradual, and it is difficult to recognize the high point. Yet, it is an indication of the poor route-finding skills of the leaders that they passed the well known landmark Green (or Pacific) Spring, and ended up at a camp without pastureage. Stanton’s letter also supports the theory that Reed made his diary entries after the fact, maybe only a day or two, maybe much later.

Thornton, with the benefit of hindsight in 1848, wrote of this day when many of the former members of the Russell Party camped on the Little Sandy:

A large number of Oregon and California emigrants encamped at this creek, among whom I may mention the following--Messrs. West, Crabtree, Campbell, Boggs, Donners and Dunbar. I had, at one time or another, became acquainted with all of these persons in those companies, and had traveled with them from Wokaruaka, and until subsequent divisions and subdivisions had separated us. We had often, since our various separations, passed and repassed each other upon the road, and had frequently encamped together by the same water and grass, as we did now. In fact, the particular history of my own journey is the general history of theirs...the greater number of the Californians, and especially the companies in which George Donner, Jacob Donner, James F. Reed, and William H. Eddy, and their families traveled, here turned to the left, for the purpose of going by way of Fort Bridges, to meet L.W. Hastings, who had informed them, by a letter which he wrote and forwarded from where the emigrant road leaves the Sweet Water, that he had explored a new route from California, which he had found to be much nearer and better than the old one, by way of Fort Hall, and the head waters of Ogden’s River, and that he would remain at Fort Bridges to give further information, and to conduct them through. The Californians were generally much elated, and in fine spirits, with the prospect of a better and nearer road to the country of their destination. Mrs. George Donner was, however, an exception. She was gloomy, sad and dispirited, in view of the fact, that her husband and other could think for a moment of leaving the old road, and confide in the statement of a man of whom they knew nothing, but who was probably some selfish adventurer.

Monday, July 20, 1846

Mo 20 this day made 5 and encamped on little Sandy within 6 miles of Big Sandy

Tuesday, July 21, 1846

Tues 21 we encamped on little Sandy all day Geo Donner lost one Steer in this encampmt J.F. Reed lost old George & one Ball faced Steer, by being poisoned at dry Sandy-on Saturday night last

Wednesday, July 22, 1846

Wed 22 left our encampmt and went to Big Sandy 6 Mr Dallin lost 1 steer from Poison on Dry sandy

Reed crossed out the following words: Tomorrow we have 28 miles to grass Big Sandy River enters a gorge below the Crossing and Consequently there is No grass.

The camp of the 22nd was on the Big Sandy was near present Farson, Wyoming, at the junction of Highways 28 and 191.

Thursday, July 23, 1846

Thus 23 encamped on big Sandy grass Plenty 13

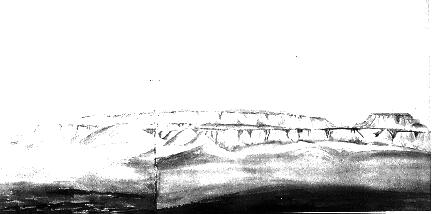

[The trail here ran though the Badlands of southwestern Wyoming, along present Highway 28.]

The Badlands

Meanwhile, back on the Trail, the Graves family made their own fateful decision

as recounted by William Graves in his 1877 article Crossing the Plains in

’46

published in the Russian River Flag: my father’s three wagons, Mr. Daniel’s one and Mr. McCracken’s one left the rest and pushed to the South Pass; there we left them, for they talked of going to Oregon and we were bound for California.

Friday, July 24, 1846

Frid 24 this day made green River in the morning and went down about 3 miles and made in all 8

Saturday, July 25, 1846

Sat 25 Started this morning Early and went down green River about 4 miles to Bridgers New fort where we turned to the Right to Blacks fork making in all 16 the fort is now vacant, Bridger having remouved to his old Fort on Blacks fork

Reed may have confused the new and old forts. Jefferson on his map shows the Old Trading Post

on the Green River a few miles above the confluence with Black’s Fork, which Reed calls the New

fort. Reed assumed that the location of Bridger’s fort in 1846 was the site of Bridger’s first fort on Black’s Fork. However, Fremont in 1843 and Joel Palmer in 1845 apparently visited a fort on Black’s Fork in between the abandoned Green River fort and the 1846 fort on Black’s Fork .

Bluffs Along Green River, drawn by James Wilkins, 1849

Sunday, July 26, 1846

Sond 26 left Blacks fork and Crossed Hams fork about 9 miles from our encampment and encamped on Black fork making this day 18

[The crossing of Ham’s Fork is at present Granger, Wyoming, on US Highway 30 just north of Interstate 80.]

Monday, July 27, 1846

Mo. 27 left this day and encamped in a beautiful Grass bottom about 1/2 mile below Bridgers Old Fort now occupied by Bridger and Vascus--making 18

Black’s Fork of the Green River, drawn by James Wilkins, 1846

Bridger’s Fort, from Stansbury’s An Expedition to the Valley of the Great Salt Lake, 1849

Trappers Jim Bridger and Louis Vasquez built their first trading post in about 1842 to support the fur trade. By 1846, they had built this third fort

in the bottom land along Black’s Fork, which they intended as a recruiting station for emigrants. Their promotional activities included the reports sent back by the emigrants, including James Reed’s letter of July 31, 1846,

I want you to inform the emigration that they can be supplied with fresh cattle by Messrs. Vasques & Bridger. They have now about 200 head of oxen, cows and young cattle, with a great many horses and mules; and they can be relied on for doing business honestly and fairly.

Greenwood’s Cut-off, opened by the Stephens Party in 1844, went due west from the Little Sandy River to the Bear River bypassing Bridger’s Fort. Bridger and Vasquez responded by promoting Hasting’s Cut-off via Salt Lake, which was reached by following the original Oregon Trail past Bridger’s fort.

Bridger’s trading post later became a Mormon fort, and then Fort Bridger, a US Army fort. It served cross-country travelers for many years. Fort Bridger is a Wyoming State Historical Site, located south of Interstate 80 east of the present town of Fort Bridger, Wyoming. The Site includes a replica of Bridger’s trading post, as well as restorations of the surviving later fort buildings. A museum contains exhibits covering the history of the various forts.

Tuesday, July 28, 1846

Tus 28 this day lay in Camp our Cattle much fatigued from the hard drive we made during the last 2 weeks

Wednesday, July 29, 1846

Wed. 29 still in Camp recruiting this day. J F Reed lost one of his best oxen Supposed to be murrin

Thursday, July 30, 1846

Thur 30 Still on Camp at Bridgers Fort on Blacks fork Our Cattl looks fine

During the stay at Bridger’s Fort, new members joined the Party. One was Jean Baptiste Trudeau, who recounted the story in the October 11, 1891 edition of the San Francisco Morning Call:

My name is Juan Baptiste Truxido, .... My parents were of French birth and I was born east of the Rockies, .... I spent my young days in the mountains and the plains .... When Fremont and Kit Carson came along on their way to California I joined them .... After leaving Fremont’s party I went to Fort Bridger, Utah, and remained there until July, 1846. The famous Donner party ... was at the fort and preparing to strike out to California. ... I was sent along by the people at the fort as a guide and guard, ....

Another new member, according to Reed’s account in the Pacific Rural Press of March 25 and April 1, 1871: Mr. McCutchen, wife and child joined us here.

Friday, July 31, 1846

Frid. 31 We Started this morning on the Cut off rout by the south of the Salt Lake-& 4 1/2 miles from the fort there is a beautiful Spring called the Blue Spring as Cold as ice passed Several Springs and Encamped at the foot of the first Steep hill going west making this day 12

[The first Steep hill

is Bridger Butte.]

On this day, James Reed wrote a letter to one of his brothers-in-law, Gersham Keyes. Reed’s optimism (completely unfounded, it would turn out) explains much of what was to befall him:

Fort Bridger, one hundred miles from the Eutaw or Great Salt Lake, July 31, 1846. .... I have replenished my stock by purchasing from Messrs. Vasques & Bridger, two very excellent and accommodating gentlemen, who are the proprietors of this trading post.--The new road, or Hastings’ Cut-off, leaves the Fort Hall road here, and is said to be a saving of 350 or 400 miles in going to California, and a better route. There is, however, or thought to be, one stretch of 40 miles without water; but Hastings and his party, are out a-head examining for water, or for a route to avoid this stretch. I think that they cannot avoid it, for it crosses an arm of the Eutaw Lake, now dry. Mr. Bridger, and other gentlemen here, who have trapped that country, say that the Lake has receded from the tract of country in question. There is plenty of grass which we can cut and put into the waggons, for our cattle while crossing it. We are now only 100 miles from the Great Salt Lake by the new route,--in all 250 miles from California; while by way of Fort Hall it is 650 or 700 miles--making a great saving in favor of jaded oxen and dust. On the new route we will not have dust, as there are about 60 waggons ahead of us. The rest of the Californians went the long route--feeling afraid of Hasting’s Cut-off. Mr. Bridger informs me that the route we design to take, is a fine level road, with plenty of water and grass, with the exception before stated. It is estimated that 700 miles will take us to Capt. Suter’s Fort, which we hope to make in seven weeks from this day.

Reed was apparently not aware of the letters left for the wagon train emigrants by Edwin Bryant. According to Bryant, on July 18 he left at Bridger’s Fort letters for his friends in the wagon trains, warning them against Hasting’s Cut-off. Reed’s opinion of Vasquez and Bridger changed considerably when he learned of Bryant’s letter. In his reminiscences published in the Pacific Rural Press on March 25 - April 1, 1871, Reed wrote:

Arriving at Fort Bridger, I added one yoke of cattle to my teams, staying here four days. Several friends of mine who had passed here with pack animals for California, had left letters with Mr. Vasques--Mr. Bridger’s partner--directing me to take the route by way of Fort Hall and by no means to go the Hastings cut-off. Vasquez, being interested in having the new route traveled, kept these letters.