February, 1847

The First Relief started from Johnson’s Ranch (east of present Wheatland, California) and followed the Wagon Road to reach the cabins. They brought some survivors back to Bear Valley. Meanwhile, the Second Relief started from San Francisco and reached the cabins.

The dated entries below are from the diary of Patrick Breen. Shortly after he moved his family into the cabin built two years earlier by the Stevens-Townsend-Murphy Party, Patrick Breen began a diary, recording in his terse fashion the events of that winter of entrapment. Upon his rescue, Breen gave his diary to George McKinstry, Sheriff and Inspector at Sutter’s Fort. McKinstry had himself traveled the Hastings Cut-off and arrived at Sutter’s Fort on October 19. McKinstry sent the diary to the California Star, which published in an abridged form on May 22, 1847. The diary has been more correctly transcribed, and published, by George Stewart in Ordeal by Hunger, Dale Morgan in Overland in 1846 and Joseph King in Winter of Entrapment. It is available online in original manuscript at the University of California, Berkeley, Bancroft Library.

The Diary of the First Relief is a copy made by Alcalde John Sinclair at Sutter’s Fort of a diary kept by M.D. Ritchie and Reasin P. Tucker. James Reed obtained Sinclair’s copy. Stewart suggests that Ritchie’s dates are one day late, because they don’t agree with Breen’s date for their arrival at the Lake.

The Diary of the Second Relief is a diary kept by Jarmes Reed. He kept the manuscript.

Patty Reed Lewis provided copies of both diaries to C.F. McGlashan in 1879 for his book. The diaries were donated to the Sutter’s Fort Historical State Park by the Reed estate in 1945. The diaries were transcribed by Carroll Hall in Donner Miscellany, and by Dale Morgan in Overland in 1846.

Monday, February 1, 1847

Mond. February the 1st- froze very hard last night cold today & Cloudy wind N W. sun shines dimly the snow has not settled much John is unwell today with the help of God & he will be well by night amen

In California, after fighting in the Battle of Santa Clara, James Reed resumed his efforts to mount a relief, as he described in his April 1, 1871 article in the Pacific Rural Press:

The road now being clear, I proceeded to San Francisco, with a petition for some of the prominent citizens of San Jose, asking the commander of the navy to grant aid to enable me to return to the mountains.

Arriving at San Francisco, I presented my petition to Commodore Hull, also making a statement of the condition of the people in the mountains as far as I knew; the number of them, and what would be needed in provisions and help to get them out. He made an estimate of the expense that would attend the expedition, and said that he would do anything within reason to further the object, but was afraid that the department at Washington would not sustain him, if he made the general out-fit. His sympathy was that of a man and a gentleman. I also conferred with several of the citizens of Yerba Bueno, their advice was not to trouble the commodore further. That they would call a meeting of the citizens and see what could be done.

Tuesday, February 2, 1847

Tuesday 2nd began to snow this morning & Continued to snow until night, sun shines out at times

Wednesday, February 3, 1847

Wend. 3rd Cloudy looks like more snow not cold, froze alittle last night, sun shines out at times.

In California, the settlers responded to appeals by James Reed, as reported in The California Star, Yerba Buena (San Francisco) of February 6:

It will be recollected that in a previous number of our paper, we called the attention of our citizens, to the situation of a company of unfortunate emigrants now in the California mountains. For purpose of making their situation more fully known to the people, and of adopting measures for their relief, a public meeting was called by the Honorable Washington A. Bartlett, Alcalde of the Town on Wednesday evening last. The citizens generously attended, and in a very short time, the sum of eight hundred dollars was subscribed to purchase provisions, clothing, horses, and mules to bring the emigrants in. Committees were appointed to call on those who could not attend the meeting, and there is no doubt but that five or six hundred dollars more will be raised. This speaks well for Yerba Buena.

The meeting was described by James Reed in his April 1, 1871 article in the Pacific Rural Press:

At the meeting, the situation of the people was made known, and committees were appointed to collect money. Over a thousand dollars was raised in the town, and the sailors of the fleet gave over three hundred dollars. At the meeting, midshipman Woodworth volunteered to go into the mountains.

Thursday, February 4, 1847

Thurd. 4th Snow.d hard all night & Still continues with a strong S:W. wind untill now. abated looks as if it would snow all day snow about 2 feet deep, now

On the other side of the mountains, the First Relief Party prepared to set out, as recorded in notes added to the end of the Diary by Reasin P. Tucker:

all hands were actively engaged until twelve o’clock on Thursday the fifth [sic] of February in completing the arrangements at that time the horses were brought up and part of them saddled when unfortunately a few of them got away and recrossed the river Mr. Sinclair having done all that could be done then called the party together and addressed a few words of encouragement to them requesting them never to turn their backs upon the Mountains until they had brought away as many of their suffering fellow beings as possible, he then left us to return home while several of the men crossed the river at the same time to bring back the horses which got away from us when the horses were brought over there was every appearance of a storm coming on the day being nearly spent the party considered it best to remain until morning rather than risk the destruction of their provisions by the rain which in a short time after fell in torrents accompanied by one of the heaviest hurricanes ever experienced on the Sacramento.

Friday, February 5, 1847

Frid. 5th snowd. hard all untill 12 O’clock at night, wind still continues to blow hard from the S.W. to day pretty clear a few clouds only Peggy very uneasy for fear we shall all perish with hunger we have but a little meat left & only part of 3 hides has to support Mrs. Reid, she has nothing left but one hide & it is on Graves shanty Milt. is livig there & likely will Keep that hide Eddys child died last night-

[Margaret Eddy was 5 years old.]

On the other side of the mountains, the First Relief Party set out from Johnson’s Ranch, as recorded in a diary entitled Notes Kept by M.D. Ritchie on the Journey to Assist the Emigrants---

10 miles would have brought the First Relief Party to near present Garden Bar Road, not far from where the Snowshoe Party likely reached the wagon road.

Names of the Party-- Capts. R. P. Tucker ---A. Glover Men Joseph Sell " R. S. Moutrie " Edward Coffymier " John Rhodes " M. D. Ritchie " Daniel Rhodes " Adolph Bruheim " George Tucker " W. H. Eddy " Wm. Coon Feby 5th 1847--First day travelled 10 miles bad roades often miring down horses and mules.

In 1847, Daniel Rhoads wrote to his father-in-law:

Finally we concluded we would go or die trying, for not to make any attempt to save them would be a disgrace to us and to California for as long as time lasted. We started, a small company of 7 men, myself, John Rhoads, Joseph Forster, Mr. Glover and some sailors. We each carried 50 pounds of provisions, a heavy blanket, tools and started.

George Tucker, who was 16 at the time, described the conditions to C.F. McGlashan in his 1879 manuscript:

We mounted our horses and started. The ground was very soft among the foothills, but we got along very well for two or three miles after leaving Johnson’s ranch. Finally, one of our pack-horses broke through the crust, and down he went to his sides in the mud.

Riley Sept

Moutrey gave this statement in the Santa Cruz Sentinel of August 31, 1888:

Ther was seven of us started Aquila Glover, Daniel Rhoades, John Rhoades, Daniel Tonker, Joe Sill, Ned Copymier and myself. We went up Bear River valley to the Johnson place, just below the snow line.

Members of Donner Relief Expedition re-enacting departure of First Relief at Johnson’s Ranch, photographed 2022

Old road off of Garden Bar Road, photographed 2022

Saturday, February 6, 1847

Satd. 6th it snowd. faster last night & to day than it has done this winter & still Continues without an intermission wind S.W. Murphy’s folks or Keysburgs say they cant eat hides I wish we had enough of them Mrs Eddy very weak

On the other side of the mountain, the First Relief continued their journey eastward:

The 6-7th days travelled 15 miles road continued bad commenced raing before we got to camp continued to rain all of that day and night very severe [15 miles brought the Party to South Wolf Creek, west of present Chicago Park.]

In 1873, Daniel Rhoads dictated an account for Prof. Bancroft:

we started on our journey, without a guide, and trusting to the judgment of our leaders, John P. Rhoads (my brother) and --- Tucker to find our way. Until we ’struck’ the snow we took the emigrant trail. ... Our road was in very bad condition and at frequent intervals we had to unpack the mules and drag them out of the mire.

Further back, George Tucker and William Eddy set out from Johnson’s ranch, having returned there the day before to retrieve the pack-horse which had run off, as Tucker described in his 1879 manuscript:

Eddy and myself started about ten o’clock. We had to travel in one day what the company had traveled in two days. About the time we started it commenced clouding up, and we saw we were going to have a storm. We went on until about one o’clock, when my horse gave out. It commenced raining and was very cold. Eddy said he would ride on and overtake the company, if possible, and have them stop. He did not overtake them until about dark, after they had camped."

South Wolf Creek in Long Ravine, photographed 2022

As the First Relief set out from Johnson’s Ranch, the Second Relief was forming in San Francisco, as described by James Reed in his April 1, 1871 article in the Pacific Rural Press:

Commodore Hull gave me authority to raise as many men, with horses, as would be required. The citizens purchased all the supplies necessary for the out-fit, and placed them on board the schooner------, for Hardy’s Ranch, mouth of Feather river. Midshipman Woodworth took charge of the schooner, and was the financial agent of the government.

In the Reed papers donated to Sutter’s Fort Museum in 1945 was the following document:

Headquarters

Northern Dept. of California

San Francisco

Feby 6th 1847

To Jas. F. Reed Esq.

Sir You are hereby appointed as assistant to Passed Mid’n Woodworth who goes in command of the Expdn. to the California Mountains. You will go with the Pilot Mr. Greenwood and urge forward his equipment and early start and then to make the best or your way to Feather River to meet Mr. Woodworth at the point of rendezvous.

You will keep a careful acct. of the necessary expenses of your expedition and submit the same to Mr Woodworth for his approval with the necessary vouchers.

Mr. Greenwood had contracted to supply twenty horses or mules and eight men including Mr. McCutchen, for the sum of eight hundred dollars one half of which has been paid by the U.S. Gov’t. or though Mr. Woodworth, the other half by the subscriptions of the people at Sonoma and Nappa; ...

As the plan of the Expedition has been fully explained and your own deep interest in it, it is not deemed necessary to be more explicit in these orders--for further instructions apply to Mr. Woodward--and your own discretion to which much must be left.

Wishing you every success and a happy meeting with your distressed family I am

Sir Your Obt Svt.

J.B. Hull

Commg. Northern Dept. of California

Caleb Greenwood of the Second Relief was an old Mountain Man, a contemporary of Jedediah Smith and Jim Bridger. Greenwood had guided the Stevens-Townsend-Murphy Party in 1844, the first party to successfully bring wagons over the Sierra Nevada. During his journey east in 1845, he discovered the Dog Valley route that bypassed the narrow upper Truckee River canyon, which he used on his return guiding 50 wagons. It was the Stevens Party’s discovery of Greenwood’s Cut-off from the Little Sandy to the Bear River that bypassed Bridger’s Fort and caused Bridger and Vasquez to promote Hastings’ Cut-off to Reed and the other emigrants of 1846.

Sunday, February 7, 1847

Sund. 7th Ceased. to snow last after one of the most Severe Storms we Experienced this winter the snow fell about 4 feet deep I had to shovel the snow off our shanty this morning it thaw so fast & thawd. during the whole storm to day it is quite pleasant wind S.W. Milt here today says Mrs Reid has to get a hide from M.rs Murphy & McCutchins child died 2nd of this Month

[Harriet McCutchen was 1 year old.]

On the other side of the mountains, the First Relief endured the rainstorm, as described by George Tucker in his 1879 manuscript:

Going up to camp, I found the men all standing around a fire they had made, where two large pines had fallen across each other. They had laid down pine bark and pieces of wood to keep them out of the water. They had stood up all night. The water was running two or three inches deep all through the camp."

In the Valley, Reed began a diary of his relief expedition:

Feby 7 1847

Sund Mo 8 left Francisco half past one oclock on Sundaye in a Launch for Sonoma and arrived on Tuesday morning.

Monday, February 8, 1847

Mond 8th fine clear morning wind S.W. froze hard last Spitzer died last night about 3 Oclock today we will bury him in the snow Mrs Eddy died on the night of the 7th

In her 1856 book California In-Doors and Out, Eliza Farnham wrote this account based on her conversations with the Breens:

One day a man came down the snow-steps of Mrs. Breen’s cabin, and fell at full length within the doorway. He was quickly raised, and some broth, made of beef and hide, ... put into his lifeless lips. It revived him so he spoke. He was a hired driver. His life was of value to no one. Those who would have divided their morsel with him, were in a land of plenty. She said that when a new call was made upon her slender store, and she thought of her children, she felt she could not withhold what she had. ... The man who had fallen in their door, died with them.

In 1879, Patty Reed wrote a letter to C.F. McGlashan:

Spitzer died ... imploring, Mrs. Breen, to put a little meat in his mouth, so he could just know, it was there, & he could die easy, & in peace. I do not think the meat was given to him, but he gave up the ghost, & was no more.

On the other side of the mountains, the First Relief had reached a camp in the hills along present South Wolf Creek: here we laid by on the 8th to dry our provisions and clothing

Tuesday, February 9, 1847

Tuesd, 9th Mrs Murphy here this morning pikes child all but dead Milt at Murphys not able to get out of bed Keyburg never gets up says he is not able. John went down to day to bury Mrs Eddy & child heard nothing from Graves for 2 or 3 days Mrs Murphy just now going to Graves fine moing wind S.E. froze hard last night begins to thaw in the Sun

On February 9, 1896, William Murphy gave a talk at Truckee, as reported in the Marysville Appeal:

Then the little child of Mrs. Eddy who, with her two children, were with us, her husband having gone with the Forlorn Hope, died, and was not buried until its mother died two days later, and they lay in this same room with us two days and nights before we could get assistance to remove their corpses to the snow.

On the other side of the mountains, the First Relief continued their journey:

9th Travelled 15 miles swam the animals one creek and carried the provisions over on a log--

15 miles would have brought the Party across Greenhorn Crossing and Steephollow Crossing, to the present Lowell Hill Ridge.

George Tucker described Steephollow Crossing in his 1879 manuscript:

This stream was not more than a hundred feet wide, but was about twenty feet deep, and the current was very swift. We felled a large pine tree across it, but the center swayed down so that the water ran over it about a foot deep. We tied ropes together and stretched them across to make a kind of hand railing, and succeeded in carrying over all out things. We undertook to make our horses swim the creek, and finally forced two of them into the stream, but as soon as they struck the current they were carried down faster than we could run. One of them at last reached the bank and got ashore, but the other went down under the tree we had cut, .... He finally struck a drift about a hundred yards below, and we succeeded in getting him out almost drowned.

Road near Greenhorn Crossing, photographed 2022

Steephollow Crossing, photographed 1987

(In 1846, Steephollow Creek was narrower and the crossing was about 50 feet below the present creek bed. The creek was significantly filled by tailings and silt washed down from hydraulic mining in the 1860’s.)

James Reed’s Diary of the Second Relief: Tus 9th Remained at Sonoma today got from Lieut. Maruey every assistance required and Ten government horses 4 Saddles & Bridles

Wednesday, February 10, 1847

Wednd. 10th beautiful morning Wind W. froze hard last night, to day thawing in the Sun Milt Elliot died las night at Murphys Shanty about 9 Oclock P.M. Mrs Reid went there this morning to see after his effects, J Denton trying to borrow meat for Graves had none to give they have nothing but hides all are entirely out of meat but a little we have our hides are nearly all eat up but with Gods help spring will smile upon us

In 1891, Virginia Reed wrote Across the Plains in the Donner Party

in Century Magazine:

When Milt Elliott died,--our faithful friend, who seemed so like a brother,--my mother and I dragged him up out of the cabin and covered him with snow. Commencing at his feet, I patted the pure white snow down softly until I reached his face. Poor Milt! it was hard to cover that face from sight forever, for with his death our best friend was gone.

On the other side of the mountains, the First Relief continued:

10th day travelled 4 miles came to the snow continued about 4 miles further animals belly deep in snow and camped at the Mule springs

In 1873, Daniel Rhoads dictated an account for Prof. Bancroft:

In about five or six miles a day we reached the snow which we found three feet deep. Through this we worried along some five miles when it became too deep for the mules to go any further it being eight feet deep and falling all the time; a regular storm having set in.

George Tucker described the camp in his 1879 manuscript:

The next day, about noon, we reached Mule Springs. The snow was from three to four feet deep, and it was impossible to go any farther with the horses. Unpacking the animals, Joe Varro and Wm. Eddy started back with them to Johnson’s Ranch. The rest of us went to work and built a brush tent in whch to keep our provisions.

Mule Springs is located on Lowell Hill Ridge, north of the Bear River across from present Baxter, California. The First Relief probably reached the snow along Lowell Hill Ridge near the Camel Hump, a steep and narrow climb on the ridge.

Camel Hump, photographed 2022

Mule Springs, photographed 2022

James Reed’s Diary of the Second Relief: 10 Weds. left this morning for Nappa with 5 men for the Mountains. 18

[As he did with his diary of the journey from present Douglas, Wyoming to Golconda Summit, Nevada, Reed ended each day’s entry with an estimate of the miles.]

Thursday, February 11, 1847

Thursd 11th fine morning wind W. froze hard last night some clouds lying in the E. looks like thaw John Denton here last night very delicate, John and Mrs Reid went to Graves this morning

On the other side of the mountains, the First Relief continued:

11th Mr Eddy started back with the animals left Wm Coon and George Tucker to guard what provision were left in camp, the other ten men each taking with the exception of one man (Mr Curtis who took about 25 pounds) about 50 lbs and travelled on through the snow having a very severe days travel over mountains making about 6 miles Camped on Bear River under a cluster of large Pines--

James Reed’s Diary of the Second Relief:

11 Thus Remained at Mr. George Yonts on acct of Greenwood here I engaged three men more and bought them Two horses. [George Yount’s ranch is the site of present Yountville, California, north of Napa.]

Friday, February 12, 1847

Frid, 12th A warm thawey morning wind S-E. we hope with the assistance of Almighty God to be able to live to see the bare surface of the earth once more O God of Mercy, grant it if it be thy holy will Amen

On the other side of the mountains, the First Relief continued: On the 12th moved camp about two miles and stopped to make Snow Shoes tried them on and found them of no benefit cast them away

Riley Sept

Moutrey gave this statement in the Santa Cruz Sentinel of August 31, 1888:

we struck snow and stopped to make snow-shoes. We left our mules and loads of provisions on the mountains there, and started up into the snow with about sixty pounds of provisions each. It were seventy miles over the divide inter Truckee canyon, where they told us the camp was. The snow was ’bout fifteen feet deep and soft. All made an average of ten mile a day.

James Reed’s Diary of the Second Relief: 12 Frd left Nappa and arrived at Mr. Childs where I bought 1 horse & 1 mule also 2 waggon Covers for Tents. 12

Joseph Chiles’ ranch was north of Yount’s, in present Chiles Valley. Joseph Chiles had arrived in California with the Bartleson-Bidwell Party in 1841, the first party to attempt to bring wagons cross country to California. That party abandoned their wagons at Relief Springs in eastern Nevada and crossed the Sierra near Sonora Pass in October. Chiles returned east in 1842, rounding the Sierra at Tejon Pass. With the Mountain Man Joseph Walker, Chiles led a wagon train to California in 1843. Chiles rode ahead on horseback in a failed attempt to resupply the wagons. The wagons were abandoned on the east side of the Sierra along the Owens River. Thus, Reed had the benefit of two of the most experienced explorers then in California--Greenwood and Chiles.

Saturday, February 13, 1847

Sat. 13th fine morning clouded up yesterday evening snowd a little & Continued cloudy all night, cleared off about daylight wind about S.W Mrs Reid has headacke the rest in health

On the other side of the mountains, the First Relief continued:

and on the 13th made Bear Valley upon digging for Curtis’s waggon found the snow ten feet deep and the provisions destroyed by the Bear. Rain and snow fell upon us that night--

Curtis had abandoned his wagon the previous Fall. James Reed and Walter Herron had come across the wagons when they rode ahead to Sutter’s Fort in October Reed and Herron rescued Mr. and Mrs. Curtis and cached flour in the wagons after the failed relief effort in November.

Bear Valley, photographed 2022

James Reed’s Diary of the Second Relief: 13 Sat this day very Rough road we encamped near Berrissas 9

[Berryessa’s Ranch is the site of present Lake Berryessa.]

Reed continued to obtain supplies, as shown in this receipt found in the Reed papers donated to Sutter’s Fort Museum in 1945:

Feby 13th 1847

Received of J E. Woodworth U States Navy pr James F Reed assistant a Receipt for one Tent valued at Two Dollars for the use of the United States on the expedition to the mountains

Witness W Bradley

her mark

X

Margrat Allen

The Monterey Californian published the first account of the tragedy that contained most of the elements of the story as told to this day:

By the arrival of the Brig Francisco, 3 days from Yerba Buena, Le Moine, Master, brings to us the heart rending news of the extreme suffering of a party of emigrants who were left on the other side of the California mountain, about 60 in all, nineteen of whom started to come into the valley. Seven, only have arrived, the remainder died, and the survivors were kept alive by eating the dead bodies. Among the survivors are two young girls. ...

We have but few of the particulars of the hardships which they have suffered. Such a state of things will probably never again occur, from the fact, that the road is now better known, and the emigrants will hereafter start and travel so as to cross the mountain by the 1st of October. The party which are suffering so much, lost their work cattle on the salt planes, on Hasiting’s cut off, a rout which we hope no one will ever attempt again.

The Yerba Buena California Star published an account which also attempted to explain the tragedy:

A company of twenty men left here on Sunday last for the California mountains with provisions, clothing &c. for the suffering emigrants now there. ... Mr. Greenwood, an old mountaineer went with the company as pilot. If it is possible to cross the mountains they will get to the emigrants in time to save them.

DISTRESSING NEWS.

By Capt. J.A. Sutter’s Launch which arrived here a few days since from Fort Sacramento--We received a letter from a friend at that place, containing a most distressing account of the situation of the emigrants in the mountains, who were prevented from crossing them by the snow--and of a party of eleven who attempted to come into the valley on foot. The writer who is well qualified to judge, is of the opinion that the whole party might have reached the California valley before the first fall of snow, if the men had exerted themselves as they should have done.

The writer of the letter to the Star was George McKinstry, who wrote the following letter to the Star on February 13:

Capt. E.M. Kern, commander of this district returned from Johnsons settlement on the 11th inst. ... he found the five women and two men that had succeeded in getting in from the unfortunate company now on the mountains, in much better health than could have been expectd; in fact they were suffering merely from their feet being slightly injured by the frost. They are living with the families of Messrs. Keyser and Sicard, and will come down to the Fort for protection as soon as they can walk. ... I hope your citizens will do all in their power to assist the unfortunate party on the mountains. All the horrid reports that they have received, part of which I wrote you in my last were corroborated by those who were so fortunate as to get in.

Sunday, February 14, 1847

Sund 14th fine morning but cold before the sun got up, now thawing in the sun wind S-E Ellen Graves here this morning John Denton not well froze hard last night

John & Edw.d burried Milt. this morning in the Snow

Virginia Reed had said that she and her mother buried Milt Elliott, but in his 1896 talk at Truckee, William Murphy confirmed Breen’s diary:

Mr. Elliott came wandering around, and took up his place with us, we sharing the remnants of the beef-hides, no, the emigrant ox hides with him. We had quite a lot of such glue making material; but mark, it would not sustain life - as listen, Elliott soon starved to death. We found some of the more able neighbors to remove his corpse from our room, and bury it in the snow.

On the other side of the mountains, the First Relief remained at Bear Valley: Morning of the 14--fine weather.

James Reed’s Diary of the Second Relief: 14 Sun left and had as usual a bad road encamped about 15 miles west of Mr Gordons up Cach River. 15

[Reed camped along Cache Creek in present Capay Valley, west of Woodland, California.]

Monday, February 15, 1847

Mond. 15 moring Cloudy, until 9 Oclock then Cleared off Sun shine wind W. Mrs Graves refusd. to give Mrs Reed any hides put Suitors pack hides on her shanty would not let her have them says if I say it will thaw it will not, she is a case

On the other side of the mountains, Reasin Tucker wrote in the diary of the First Relief:

From this on the journal was kept by Mr R. P. Tucker

15th Fine day three of our men declined going any further W. D. Ritchie A. Bruheim--Curtis only 7 men being left the party was somewhat discouraged we consulted together and under existing circumstances I took it upon myself to insure every man who persevered to the end five dollars per day from the time they entered the snow we determined to go ahead and that night camped on Juba after traveling 15 miles--

15 miles would have brought the party to the Yuba River about where the Trail comes down from Cascade Lake. More likely, the party made only 11 miles to where the wagon road left the Yuba River below Cisco Butte.

Stewart suggested that the Relief Parties did not make the difficult climb from Bear Valley up to Emigrant Gap. He suggested that they crossed from the Bear River to the Yuba River at the upper end of Bear Valley and followed the Yuba River to the Yuba Bottoms

at Cisco Butte. Although T.H. Jefferson’s Map of 1846 incorrectly shows the Yuba River flowing into the Bear River, it confirms that the emigrants knew that the Yuba River could be followed east from Bear Valley. Ascending the Yuba River (now flooded by Lake Spaulding) might have been easier than climbing the ridge to the Gap. However, it is more likely that they avoided the steep climb by staying north of the ridge (the route of present Route 20) to Yuba Pass, and from there east to the Yuba River below Cisco Butte (the route of present I-80).

Yuba River near Cisco Butte, photographed 2022

In 1847, Daniel Rhoads wrote to his father-in-law: After we reached the mountains the snow was 5 to 25 feet deep. We made snow shoes out of pine boughs. At the end of our day’s travel we cached some provisions to have on our way back.

In 1873, Daniel Rhoads dictated an account for Prof. Bancroft:

Our encountering the snow so deep and so much sooner than we had been led to anticipate utterly disheartened some of the party and six men turned back. We made a camp and left the mules in charge of one of Sutter’s men a German who went by the soubriquet of ’Greasy Jim’ Jim was to take care of the animals and to pasture them on hill sides with a Southern exposure and such other bare spots as he could find, until our return. Our party now consisted of seven, John P. Rhoads, ___ Tucker (now in Napa valley), Sept. Mootry (now in Santa Clara), ___ Glover (dead), a sailor named George Foster, a sailor named Mike, and myself. Each man made a pair of snowshoes. These were constructed by cutting pine boughs, stripping off the bark, heating them over the fire and bending them in the shape of an ox-bow about two feet long and 1 wide with a lattice work of raw hide, for soles. We attached them to our feet by means of the rawhide strips with which we were provided. On these we had to travel continuously except at brief intervals on hill-sides & bare spots where we took them off. Each man also took a single blanket a tin cup, a hatchet and as near as the captains could estimate 75 pounds of dried meat. Thus equipped we started. Foster had told us that we should find the emigrants at or near Truckee Lake, (Since called Donner Lake) and in the direction of this we journeyed.

James Reed and the Second Relief continued:

15 Mo had a good Road and encamped about 1 o’clock opposit Mr. Gordons’ on account of high water in Cach River 15 [Gordon’s ranch was on the north bank of Cache Creek north of present Woodland, California.]

Tuesday, February 16, 1847

Tuesd. 16th Commenced. to rain yesterday Evening turned to Snow during the night & continued until after daylight this morning it is now sun shine & light showers of hail at times wind N. W by W. we all very weakly today snow not getting much less in quantity

On the other side of the Pass, the First Relief approached: 16 Traveling very bad and snowing, made but 3 miles and camped in snow 15 feet deep--

[3 miles would have brought the party to Hampshire Rocks along the Yuba.]

James Reed and the Second Relief continued on: 16 Tues Crossed Cach river water up to the backs of our horses I went to Wm Gordons and bought 5 horses, returned to the men and traveled about 4 miles. 4

Wednesday, February 17, 1847

Wedd. 17th froze hard last night with heavy clouds running from the N. W. & light showers of hail at times today same kind of Weather wind N. W. very cold & Cloudy no sign of much thaw

On the other side of the Pass, the First Relief weathered the storm: 17 Travelled 5 miles--

[5 miles, or likely less, would have brought the Party to Cascade Creek where the road left the Yuba and climbed the ridge to the south of present Kingvale.

In 1873, Daniel Rhoads dictated an account for Prof. Bancroft:

Of course we had no guide and most of our journey was through a dense pine forest but the lofty peak which overlooks the lake was in sight at intervals and this and the judgment of our two leaders were our sole means of direction ... For the guidance of those who might follow us and as a signal to any of the emigrants who might be straggling about in the mountains as well as for our own direction on our return trip; we set fire to every dead pine tree on and near our trail At the end of every three days journey (15 or 20 miles) we made up a small bundle of dried meat and hung it to the bough of a tree to lighten the burden we carried and for subsistence on our return. ... At Sunset we ’made Camp’ by felling pine saplings 6 inches in diameter and cutting them off about 12 feet long, & placing them on the snow making a platform 6 or 8 feet wide. On this platform we kindled our fire, and dozed through the night the best way we could. If we had made the fire on the top of the snow without the intervention of any protecting substance we should have found our fire, in the morning 8 or 10 feet below the surface on which we encamped.

James Reed and the Second Relief continued on:

17 Wed left Camp early I left the Caravan and went a head to Mr. Nights where I found the water was high in the Sacramento and the Sliews swimming left here and proceeded to Mr. Hardys at the mouth of Feather river where we encamped for the night ... here I hoped to meet our supplies with Comdr Woodworth in a Launch sent from Yerba buena, but unfortunately the head winds prevented his arrivalKnight’s Landing is on the Sacramento River 21 miles northwest of Sutter’s Fort (present Sacramento). The Feather River enters the Sacramento River approximately five miles east of Knight’s Landing.

Thursday, February 18, 1847

Thur.y 18th Froze hard last night today clear & warm in the sun cold in the shanty or in the shade wind S. E all in good health Thanks to Almighty God Amen

The First Relief reached the other side of the Pass:

18thTraveled 8 miles and camped on the head of Juba on the Pass we suppose the snow to be 30 foot deep-- [The head of the Yuba is a small lake in summer, a snow covered flat in winter, just below the Pass.]

Snow Flat on West Side of Donner Pass, photographed 1997

(The low spot on the ridge is the Pass)

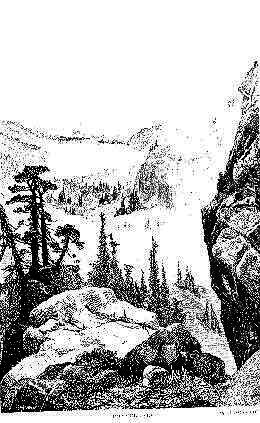

View of Donner Lake from Donner Pass, drawn by Thomas Moran

View of Donner Lake from Donner Pass, photographed 1997

The dark rock buttress on the south of the Pass (the right side of the drawing and photograph) is the the north face of Donner Peak, the lofty peak which overlooks the lake,

used to guide the First Relief Party according to Daniel Rhoads’ 1873 account.

Rhoads continued:

We went on making from four to six miles per day leaving a very sinuous trail by reasons of the impossibility of pursuing a straight course through the dense forest and of our having to wind around the sides of hills and mountains instead of going over them. The snow increased as we proceeded until it amounted to a depth of eighteen feet as was afterwards discovered by the stumps of the pine trees we burned. We travelled in Indian file. At each step taken by the man in front he would sink in the snow to his knees and of course had to lift his foot correspondingly high for his next step. Each succeeding man would follow in the tracks of the leader.--The latter soon became tired and fell to the rear and the second man took the head of the file. When he became fatigued by breaking the track he would fall back & so on each one in his turn.

James Reed and the Second Relief continued on:

18 Thur We broke Camp this morning intending to cross the Sacramento at the mouth of Feather River in Skin Boats, ... we ware relieved of the trouble by Mr. McCoon who had his Launch at Mr. Hardy’s and kindly offered her to cross our Bagage when I found our supplies had not arrived I Crossed my horse and proceeded to Mr. Johnsons, 25 miles distant for the purpose of having prepared flour and Beef. 25 [Johnson’s Ranch was on the north side of Bear River east of present Wheatland]

Friday, February 19, 1847

Frid. 19th froze hard last night 7 men arrived from California yesterday evening with som provisions but left the greatest part on the way to day clear & warm for this region some of the Men are gone to day to Donnos Camp will start back on Monday

[Diary of

Patrck Breen.]

19th at sundown reached the Cabins and found the people in great distress such as I never before witnessed there having been twelve deaths and more expected every hour the sight of us appeared to put life into their emaciated frames

[Diary of the First Relief.]

Arrival of the First Relief

Members of Donner Relief Expedition re-enacting the First Relief hiking to the Lake, photographed 2022

In 1847, Daniel Rhoads wrote to his father-in-law: We were seven days going to them. The people were dying every day. They had been living on dead bodies for weeks.

In 1873, Daniel Rhoads dictated an account for Prof. Bancroft:

At sunset on the 16th day we crossed Truckee lake on the ice and came to the spot where we had been told we should find the emigrants. We looked all around but no living thing except ourselves was in sight and we thought that all must have perished. We raised a loud halloo and then we saw a woman emerge from a hole in the snow. As we approached her several others made their appearance in like manner coming out of the snow. They were gaunt with famine and I never can forget the horrible, ghastly sight they presented. The first woman spoke in a hollow voice very much agitated & saidare your men from California or do you come from heaven.... We gave them food very sparingly and retired for the night having some one on guard until morning to keep close watch on our provisions to prevent the starving emigrants from eating them which they would have done until they died of repletion.

Riley Sept

Moutrey gave this statement in the Santa Cruz Sentinel of August 31, 1888:

On the 18th of February we crossed the summit and made down the other side toward Truckee lake.

About sundown me and Mr. Glover saw the cabins and tents o’ their party. We come nigh on fifty yard to ’em before we saw ’em. Ther camp stood ’bout sixty yards from the east end of the lake that’s now called Donner. The snow was about twelve to fourteen feet deep an’ covered everything. Where the water was ther’ war a broad, clean sheet of snow.

No one come up to greet us but when we got nearer an’ yelled, they came tumbling out of the cabins.

They were an awful looking sight--a white and starved looking lot, I can tell you. There were pretty glad to see us. They took on awful, anyhow. Men, wimmen and children crying and prayin’.

After we was there a bit they told us how the had suffered for months. The food all gone an’ death takin’ ’em on all sides.

Then they showed us up into their cabins, and we saw the bodies of them who had gone. Most of the flesh was all stripped off an’ eaten. The rest was rotten It was just awful. Ten war already dead and we could see some of ther others was going. They were too weak ter eat, an’ our pervisions bein’ scant, we thought it were best to let ’em go an’ look after th’ stronger ones.

We had ter guard the pervisions close, or they would have just swooped down and stolen ’em all. We slept there that night and gave out as much food as we could,

Moutrey embellished the story, as there are no other accounts of cannibalism at the Lake cabins before the arrival of the First Relief.

Thirteen year old Virginia Reed wrote to her cousin on May 16, 1847:

we had not ate any thing for 3days & we had onely a half a hide and we was out on top of the cabin and we seen them a coming O my Dear Cousin you dont now how glad i was, we run and met them one of them we knew we had traveled with them on the road

In 1891, Virginia Reed wrote in Across the Plains in the Donner Party

in Century Magazine:

On the evening of February 19th, 1847, they reached our cabins, where all were starving. They shouted to attract attention. Mr. Breen, clambered up the icy steps from our cabin, and soon we heard the blessed words,Relief, thank God, relief!There was joy at Donner Lake that night, for we did not know the fate of the Forlorn Hope and we were told that relief parties would come and go until all were across the mountains. But with the joy sorrow was strangely blended. There were tears in other eyes than those of children; strong men sat down and wept. For the dead were lying about on the snow, some were even unburied, since the living had not had strength to bury their dead.

William Graves was 17 at the time. His father, two sisters and brother-in-law had left with the Snowshoe Party in December. Only his sisters survived. In May, 1877, he described the arrival of the First Relief in Crossing the Plains in ’46

in the Russian River Flag:

They arrived about 8 o’clock ... and told us that father and his party all got through alive, but they froze their feet, and were so badly fatigued they could not come back with them. They said they would start back Monday or Tuesday and take all that were able to travel. Mother had four small children who were not able to travel, and she said I would have to stay with them, and get wood to keep them from freezing. I told her I would cut enough wood to last til we could go over and get provisions and come back and relieve them; to which she agreed, and I chopped about two cords.

On the other side of the mountains, James Reed and the Second Relief halted: 19 Frid I was at Johnsons to day the boys had not arrived being detained in Crossing on nect of the high winds which arose when I landed on the East side.

Saturday, February 20, 1847

Saturd. 20th pleasant weather

[Diary of Patrck Breen.]

20th My self and two others went to Donnors camp 8 miles and found them in a starving condition the most of the men had died one of them leaving a wife and 8 children, the two families had but one beef head amongst them, there was two cows buried in the snow but it was doubtful if they would be able to find them we left them telling them that they would soon have assistance if possible on the road back I gave out but struggled on until sundown when I reached the other cabins--

[Diary of the First Relief.]

Location of Donner family camp on Alder Creek, photographed 2022

On the other side of the mountains, James Reed and the Second Relief prepared: 20 Sater Still at Mr Johnsons preparing Beef by drying and Keeping his Indians at work Night & Day Grinding in a small hand mill

Sunday, February 21, 1847

Sund 21st Thawey warm day

[Diary of Patrick Breen.]

There was no entry for the 21st in the Diary of the First Relief. Likely, Tucker spent the night of the 20th at the Donner camp and returned on the 21st. As recounted by Daniel Rhoads in 1873:

The morning after our arrival John P. Rhoads and Tucker started for another camp distant 8 miles East, where were the Donner family, to distribute what provisions could be spared and to bring along such of the party as had sufficient strength to walk. They returned bringing four girls and two boys of the Donner family and some others.

C.F. McGlashan described those from the Donner camp who were brought along by the First Relief:

... let us glance at the parting scenes at Alder Creek. It had been determined that the two eldest daughters of George Donner should accompany Captains Tucker’s party. George Donner, Jr., and William Hook, two of Jacob Donner’s sons, Mrs. Wolfinger, and Noah James were also to join the company. This made six from the Donner tents. Mrs. Elizabeth Donner was quite able to have crossed the mountains, but preferred to remain with her two little children, Lewis and Samuel, until another and larger relief party should arrive. These two boys were not large enough to walk, Mrs. Donner was not strong enough to carry them, and the members of Captains Tucker’s party had already agreed to take as many of the little ones as they could carry.

George Donner’s two eldest daughters from a previous marriage were Elitha Cumi, 14, and Leanna, 12. George, Jr., was 9, Samuel was 3 and Lewis was 3. Staying with Tamsen Donner were Frances, 6, Georgia, 4, and Eliza, 3. Staying with Elizabeth were Mary, 7, and Isaac, 5.

In her 1911 book Expedition of the Donner Party and Its Tragic Fate, Eliza Donner, who was only four years old at the time of the events, wrote:

Sixteen-year-old John Baptiste was disappointed and in ill humor when Messrs. Tucker and Rhoads insisted that he, being the only able-bodied man in the Donner camp should stay and cut wood for the enfeebled, until the arrival of other rescuers. The little half-breed was a sturdy fellow, but he was starving, too, and thought that he should be allowed to save himself. After he had a talk with father, however, and the first company of refugees had gone, he became reconciled to his lot, and served us faithfully. He would take us little ones up to exercise upon the snow, saying that we should learn to keep our feet on the slick, frozen surface, as well as to wade through slush and loose drifts. Frequently, when at work and lonesome, he would call Georgia and me up to keep him company, and when the weather was frosty, hew would bringOld Navajo,his long Indian blanket, and roll her in it from one end, and me from the other, until we would come together in the middle, like the folds of a paper of pins, with a face peeping above each fold. Then he would set us upon the stump of the pine tree while he chopped the trunk and boughs for fuel. He told us that he had promised father to stay until we children should be taken from the camp, also that his home was to be with our family forever. One of his amusements was to rake the coals together nights, then cover them with ashes, and put the large camp kettle over the pile for a drum, so that we could spread our hands around it, to get just a little warm before going to bed.

In 1879, Leanna Donner wrote to C.F. McGlashan:

Mother says: Never shall I forget the day when my sister Elitha and myself left our tent. Elitha was strong and in good health, while I was so poor and emaciated that I could scarcely walk. All we took with us were the clothes on our backs and one thin blanket, fastened with a string around our necks, answering the purpose of a shawl in the day-time, and which was all we had to cover us at night. We started early in the morning, and many a good cry I had before we reached the cabins, a distance of about eight miles. Many a time I sat down in the snow to die, and would have perished there if my sister had not urged me on, saying,The cabins are just over the hill.Passing over the hill, and not seeing the cabins, I would give up, again sit down and have another cry, but my sister continued to help and encourage me until I saw the smoke rising from the cabins; then I took courage, and moved along as fast as I could. When we reached the Graves cabin it was all I could do to step down in the snow-steps into the cabin. Such pain and misery as I endured that day is beyond description.

Hills west of Donner family camp, beginning of road to lake cabins, photographed 2022

On the other side of the mountains, the Second Relief caught up to James Reed at Johnson’s Ranch:

Sundy 21 this morning the men arrived with out any accident excepting one horse that run back I got him from Mr Combs at Mr Gordons. I kept fire under the Beef all night which I had on the Scafold

Monday, February 22, 1847

Mond 22nd the Californians started this morning 24 in number some in a very weak state fine morning wind S. W. for the 3 last days Mrs Key burg started & left Keysburg here unable to go I Burried pikes Child this Moring in the snow it died 2 days ago, Paddy Reid & Thos. Came back Messrs Grover & Mutry

The Diary of the First Relief: 22d Left camp with twenty three of the sufferers 2 of the children soon gave out and two of our men carried them back and left them with Mr. Brin they were children of Mrs. Reed

Riley Sept

Moutrey gave this statement in the Santa Cruz Sentinel of August 31, 1888:

We took twenty-one of ’em; mostly wimmen and children. The strong ones we chose, as we couldn’t get the weak ones across. They were bound to die, so we left ’em. It was pitiful to hear ’em cryin’ for us, but we had to go. It was sure death to stay there.

Thirteen year old Virginia Reed wrote about the First Relief to her cousin on May 16, 1847:

thay staid thare 3 days to recruet a little so we cold go thare was 20 started all of us started and went a piece and Martha and Thomas giv out & so the men had to take them back ma and Eliza James & I come on and o Mary that was the hades thing yet to come on and leiv them thar did not now but what thay would starve to Death Martha said will ma if you never see me again do the best you can the men said thay could hadly stand it it maid them all cry but they said it was better for all of us to go on for if we was to go back we would eat that much more from them thay give them a littel meat and flore and took them back and we come on

In 1873, Daniel Rhoads of the First Relief wrote an account for H.H. Bancroft: The next morning we started on our return trip accompanied by 21 emigrants mostly women & children.

In 1896 William Murphy gave a lecture at Truckee, as reported in the Marysville Appeal: The first night out I found my feet swollen so that I feared to remove my shoes,

On the other side of the mountains, the Second Relief set out:

... and next morning by Sun rise I had about 200 lbs dryed and baged we packed our horses and started with the addition of 5 men and one Indian, our supplies 700 lbs flour including what Greenwood had dried Sunday 4 1/2 Beeves 25 horses in all 17 men in my party and Mr Greenwood had 3 Men including himself- & 2 boys traveled this day about 10 miles [Ten miles would have brought the Party to the foothills between present Camp Far West Reservoir and Lake of the Pines.]

Tuesday, February 23, 1847

Tuesd. 23 froze hard last night today fine & thawey has the appearance of Spring all but the deep Snow wind S. S. E. shot Towser today & dressed his flesh Mrs Graves Come here this morning, to borrow meat dog or ox they think I have meat to spare but I know to the Contrary they have plenty hides I live principally on the same

The First Relief continued over the mountains: 23 Got to the first cash and found half of the contents taken by the Bear being on short allowance death stared us in the face. I made an equal divide and charged them to be careful--

[This first cache was located at the Pass]

Snow Flat on West Side of Donner Pass, photographed 1997

(The low spot on the ridge is the Pass)

Riley Sept

Moutrey gave this statement in the Santa Cruz Sentinel of August 31, 1888:

We had good luck all the way over the divide. We had gone over in soft snow and our tracks had froze hard, giving us a clear trail back. Four of ther’ children, that were almost gone, we took turns in carryin’ on our backs. The rest walked.

Thirteen year old Virginia Reed wrote about the First Relief to her cousin on May 16, 1847:

we went over great hye mountain as steap as stair steps in snow up to our knees litle James walk the hole way over all the mountain in snow up to his waist, he said every step he took he was a gitting nigher Pa and something to eat the Bears took the provision the men had cashed and we had but very little to eat

In 1877, William Graves’ memoir Crossing the Plains in ’46

was published

in the Russian River Flag:

The relief had left part of their provisions on top of the mountain, thinking to have it on their return and save packing it down and up the mountain; and leaving everything with those behind, made calculations to reach their deposit the first day, which we did, tired and hungry; but, lo, and behold! there was nothing there. The fishers (a mountain animal), had torn it down and devoured it, so thechildrenhad to got to bed without their supper. But thebed!what do you suppose it was? soft enough, deep enough and as white as any swan’s down; but no blanket to cover; and we were in that fix for four more days, before we could see bare ground.

Further down the mountains, James Reed and the Second Relief moved up: 23 Tues left camp early this morning and packed today and encamped early on acct grass tomorrow we will reach the snow 20

[Twenty miles would have brought the Party to near Steephollow Crossing.]

Steephollow Crossing, photographed 1987

(In 1846, Steephollow Creek was narrower and the crossing was about 50 feet below the present creek bed. The creek was significantly filled by tailings and silt washed down from hydraulic mining in the 1860’s.)

Wednesday, February 24, 1847

Wend. 24th froze hard last night to day Cloudy looks like a storm wind blows hard from the W. Commenced thawing there has not any more returned from those who started to cross the M.ts

The First Relief continued over the mountains:

24thstarted 3 men on ahead of the Company--We had travelled about two miles when one man gave out (John Denton) I waited for him some time but in vain he could go no further I made him a fire and chopped some wood for him when I very unwillingly left him telling him he should soon have assistance but I am afraid he would not live to see it travelled 7 miles and campDenton was left by the Trail in Summit Valley, near present Norden. The Party continued on and camped on the Yuba River near present Kingvale.

Leaving the Weak (John Denton) to Die

In 1873, Daniel Rhoads of the First Relief wrote an account for H.H. Bancroft:

On the third day an emigrant named John Denton, exhausted by starvation and totally snow-blind, gave out. He tried to keep up a hopeful & cheerful appearance, but we knew he could not live much longer. We made a platform of saplings, built a fire on it, cut some boughs for him to sit upon and left him. This was imperatively necessary.

William Graves wrote in his 1877 article Crossing the Plains in ’46

: about noon, the third day, John Denton got snowblind, and could not travel, so we had to leave him on the snow, to suffer the worst of deaths.

Approaching from the other side of the mountains, James Reed and the Second Relief: 24 Weds encamped at the Mule Springs this evening mad preparations to take the snow in the morning there is left at camp our saddles Bridles etc 15

Thursday, February 25, 1847

Thursd. 25th froze hard last night fine & sun shiney to day wind W. Mrs Murphy says the wolves are about to dig up the dead bodies at her shanty, the nights are too cold to watch them, we hear them howling

When she was writing her 1911 book The Expedition of the Donner Party, Eliza Donner Houghton, daughter of George and Tamsen Donner, took notes of conversations with her sisters, including this statement from Georgia Donner, who had been five years old in 1846:

In the Mts. I used to sit in mother’s lap each morning to have my hair combed and as she brushed out the tangles she kept my attention engaged with the stories of Joseph and his cruel brethren, Daniel in the lion’s den, and Elijah and the ravens, the cruel of oil and the meat which never grew less. She also spoke of my Aunt Elizabeth and wanted me to love her.

The Diary of the First Relief: 25th This day a child died and was buried in the snow travelled 5 miles and there met with some provisions half of a cash small allowance--

[The child was 3 year old Ada Keseburg. Five miles would have brought the Party to present Cisco Butte.]

In 1873, Daniel Rhoads of the First Relief wrote an account for H.H. Bancroft: John Rhoads carried a child in his arms which died the second night.

William Graves wrote in his 1877 article Crossing the Plains in ’46

: The second day, Mrs. Keisburg offered twenty-five dollars and a gold watch to anyone who would carry her child through; but it died that night and was buried the next morning in the snow.

Cisco Butte, photographed 2022

Approaching from the other side of the mountains, James Reed and the Second Relief:

25 Thus Started with 11 horses & mules lightly packed about 80 lbs traveled about 2 miles and left one Mule, and pack, made this day with hard labour for the horses, in the snow, about 6 miles Our start was late [Six miles would have brought the party to just below Bear Valley.]

Friday, February 26, 1847

Frid 26th froze hard last night to day clear & warm Wind S:E. blowing briskly Marthas jaw swelled with the tooth ache; hungry times in camp, plenty hides but the folks will not eat them we eat them with a tolerable good appetite, Thanks be to Almighty God, Amen Mrs Murphy said here yesterday that thought she would Commence on Milt. & eat him, I dont that she has done so yet, it is distressing The Donnos told the California folks that they Commence to eat the dead people 4 days agoe, if they did not succeed that day or next in finding their cattle then under ten or twelve feet of snow & did not know the spot or near it I suppose They have done so ere this time

The Diary of the First Relief:

26--at noon had a small divide of shoe strings roasted and eat them and then proceeded about half a mile when we met two of our men with provisions we struck fire and feasted on our dry beef when we travelled about one mile farther and camped-- [The Party probably camped near present Yuba Pass.]

Approaching from the other side of the mountains, James Reed and the Second Relief:

26 Frid left our encampment early thinking the snow would bare the horses. proceeded 200 yard with difficulty when we ware Compelled to unpack the horses and take the provisions on our backs here for a few minutes there was silence with the men when the packs were ready to sling on the back when the hilarity Commenced as usual Made the head of Bear Valley a distance of 15 miles we met in the vally about 3 miles below the Camp Messrs Glover & Road belonging to the party that went to the lake for the people who Informed me they had Started with 21 persons 2 of whom had died John Denton of Springfield Ils & a Child of Keesberger Mr Glover Sent 2 men back to the party with fresh provisions they men ware in a Starving Condition and all nearly give out I here lightened our packs with a sufficiency of provisions to do the people when they should arrive,

Saturday, February 27, 1847

Sat. 27th beautiful morning sun shineing brilliantly, wind about S. W. the snow has fell in debth about 5 feet but no thaw but the sun in day time it freezing hard every night, heard some gees fly over last night saw none

The Diary of the First Relief:

27th Travelled 4 miles and met with another Company hear Mr. Reed met with his wife and two children the meeting was very affecting; travelled about 3 miles farther and camped in our old camp head of Bear Valley here we found plenty of provisions and was waited on by Mr. Thompson a man of good feeling and judgement-- [The meeting of the Reed family occurred near present Yuba Gap.]

Thirteen year old Virginia Reed wrote to her cousin on May 16, 1847:

when we had traveld 5 days travel we met Pa with 13 men going to the cabins o Mary you do not nou how glad we was to see him we had not seen him for 6 months we thought we woul never see him again he heard we was coming and he made some seet cakes he said he would see Martha and Thomas the next day

William Graves described the camp at Bear Valley in his 1877 article Crossing

the Plains in ’46

:

There were about two feet of snow there, but the first relief party had shoveled it away from the ground in a circle of about twenty feet in diameter and then cut and spread down small pine boughs for us to sleep on, which was an improvement on the five previous nights. They had packed supplies to this camp on horses and mules and then took the animals back some twenty miles to grass. We staid at Bear Valley Camp two days, ...

Bear Valley looking west, photographed 2022

The Diary of the Second Relief:

and started a man back on evening of 27 to bring more by tomorrow & 27 Sat I Sent back to our camp of the 26 2 men to bring provisions for the people they will return tomorrow and left one man to prepare for the people which ware expected today and I left Camp early on a fine hard snow and proceeded about 4 miles when we met the poor unfortunate Starved people, as I met them Scattered allong the snow trail I distributed Sweetbread that I had backed the 2 nights previous I give in small quantities, here I met my own wife Mrs. Reed and two of my little children two still in the mountains, I cannot describe the death like look they all had Bread Bread Bread was the begging of evry Child and grown person I give to all what I dared and left for the sene of desolation and now I am Camped within 25 miles which I hope to mak this night and tommorrow we had to camp soon on account of the softness of the snow, the men falling into their middles One of the Party that passed us to day a little boy Mrs Murphy’s son was nearly blind, when we met them. they ware overjoyed when we told them there was plenty of Provisions at Camp I made a Cach 12 miles and encamped 3 mi eastward on Juba, snow about 15 feet. 15 miles

After meeting the First Relief, the Second Relief reached the Yuba River Bottoms, where they made a cache. 15 miles would have brought them to where the Trail left the Yuba River near present Kingvale.

James Reed sent sent notes of his travels to J.H. Merryman, who published them as Narrative of Suffering Of a Company of Emigrants

in the December 9, 1847 Illinois Journal:

Just before reaching camp the following day, they met Messrs. Glover and Rhodes of the party fitted out by Sinclair, Sutter, and McKinstry, who informed them that they had reached the cabins and found the people in the worst condition possible; that they had started for the settlements with twenty-one persons, old and young, but owing to the robbery of their cache by a vicious little animal, called Marten, their provisions had become exhausted, and that they had left the party in a starving condition several miles behind. Receiving this information, Mr. Reed immediately dispatched Messrs. Richie and Gordon to the Mule springs to bring up the provisions cached there, and with instructions that if they should meet Mr. Woodworth to send him on with all speed, for upon him Mr. Reed greatly depended for future supplies, knowing that the quantity he had himself was insufficient for the support of the sufferers from the cabins to the settlements.

Sunday, February 28, 1847

Patrick Breen’s diary: Sund. 28th froze hard. last night to day fair & sun shiney wind S. E. 1 Solitary Indian passed by yesterday come from the lake had a heavy pack on his back gave me 5 or 6 roots resembling Onions in shape taste some like a sweet potatoe, all full of little tough fibres

In her 1856 book California, In-Doors and Out, Eliza Farnham wrote that Mr. Breen says:

About this time an incident occurred which greatly surprised us all. One evening, as I was gazing around, I saw an Indian coming from the mountains. He came to the house and said something which we could not understand. He had a small pack on his back, consisting of a fur blanket, and about two dozen of what is called California soaproot, which, by some means, could be made good to eat. He appeared very friendly, gave us two or three of the roots, and went on his way. When he was going I could never imagine. He walked upon snow-shoes, the strings of which were made of bark. He went east; and as the snow was very deep for many miles on all sides, I do not know how he passed the nights.

The First Relief was at Bear Valley: 28th remained in camp but after all our precaution three of the party eat to excess and had to be left in the care of an attendant--

In 1873, Daniel Rhoads of the First Relief wrote an account for H.H. Bancroft:

When we reached the camp where we had left our mules we remained until the next day During the night, the food in Camp not being guarded sufficiently, the eldest boy of the Donner family managed to eat so much dried meat that he died the next day [The boy was 12 year old William Hook, Elizabeth Donner’s son from a previous marriage.]

In 1877, William Graves wrote in his article Crossing the Plains in ’46

: On the fifth day, about ten o’clock, I and some of the stronger, reached camp where the provisions were; but the weaker ones did not get in till night. Wm. Donner ate so much he died the next day about 10 o’clock.

In 1896 William Murphy gave a lecture at Truckee, as reported in the Marysville Appeal:

at at Bear Valley, my sister who was with me, cut my shoes off my feet, when they swelled so that I could not put them into men’s moccasins; and being unable as I thought, to walk I was left there, until the party [William Hook] died, when the nurse left with him determined to go, as provisions had failed, and we were in need of relief. So I took the biscuits and jerked beef out of the pocket of the corpse, which furnished us food on our journey of two days. I found I could walk when then was no place to stay and as I followed the snow I could get along, though I was barefooted when I came to camp, and my blood marked my trail. I was eleven and a few days old.

The Diary of the Second Relief:

28 Sund left Camp about 12 o’clock at night and was Compl to Camp about 2 o’cl, the Snow Still being soft. left again a bout 4 all hands and made this day 14 miles in camp early Snow soft, Snow her 30 feet 3 of my men Cady, Clark & Stone kept on during the night which they intended but halted to within 2 miles of the Cabins and remained without fire during the night on acct of 10 Indians which they saw the boys not having arms and supposed they had taken the cabins and destroyed the people in the morning they started and arrived all alive in the houses give provisions to Keesberger, Brinn, Graves and two then left for Donners a distance of ten miles which they made by the middle of the day I came up with the Main body of my party Informed the people that all who ware able Should have to Start day after tomorrow made soup the infirm washed and clothed afresh Mrs Eddy & Fosters with Keesbergs people Mr Stone to cook and watch the eating of Mrs Murphy Keesberge & 3 children"

Reed’s reference to Mrs Eddy & Fosters

is a reference to their surviving children, James Eddy, 3, and George Foster, 4. Mrs. Foster had left with the Snowshoe Party, and Mrs. Eddy had died at the cabin on February 7. Reed’s use of the term the eating of Mrs Murphy...

is unfortunate, in that he means the feeding of the people in the cabin, and is not referring to cannibalism.

James Reed sent sent notes of his travels to J.H. Merryman, who published them as Narrative of Suffering Of a Company of Emigrants

in the December 9, 1847 Illinois Journal:

they saw the top of a cabin just peering above the silvery surface of the snow. As they approached it, Mr. Reed beheld his youngest daughter, sitting upon the corner of the roof, her feet resting upon the snow. Nothing could exceed the joy of each, and Mr. Reed was in raptures, when on going into the cabin he found his son alive. The family at this cabin still had a little provisions left from the supplies furnished by Mr. Glover. His party immediately commenced distributing their provisions among the sufferers, all of whom they found in the most deplorable condition. Among the cabins lay the fleshless bones and half eaten bodies of the victims of famine.

Meeting of Patty Reed and her Father

In his 1871 article in the Pacific Rural Press, Reed wrote:

we traveled all this night, and about the middle of the next day we arrived at the first Camp of Emigrants, Being Mr. Breen’s. If we left any provisions here, it was a small amount. He and his family not being in want. We then proceeded to the camp of Mrs. Murphy, where Keysburg and some children were. Here we left provisions and one of our company to cook [for] and attend them. From here we visited the camp of Mrs. Graves, some distance further east.

McGlashan’s book contains this account:

Nicholas Clark, who now resides in Honey Lake Valley, Lassen County, California, says that as he and Cady were going to the Donner tents, they saw the fresh tracks of a bear crossing the road. In those days, there were several little clumps of tamarack along Alder Creek, just below the Donner tents, and as the tracks led towards them, Mr. Clark procured a gun and started for an evening’s hunt among the tamaracks. He found the bear and her cub within sight of the tents, and succeeded in severely wounding the old bear. ... For a long distance, over the snow and through the forests, Clark followed the wounded animal and her cub. The approach of darkness at last warned him to desist,.... Early next morning, Clark again set out in pursuit of the bear, ... The endurance of the wounded animal was too great, however, and late in the afternoon he realized that it was necessary for him to give up the weary chase, ...