December 1846

While most of the Donner Party remained at the camp by the Lake, the Snowshoe Party set out to reach the settlements. They crossed the mountains to a deep canyon where they were trapped for a week by a raging storm. When they were able to travel again, they thought they could see the Central Valley of California.

The dated entries below are from the diary of Patrick Breen. Shortly after he moved his family into the cabin built two years earlier by the Stevens-Townsend-Murphy Party, Patrick Breen began a diary, recording in his terse fashion the events of that winter of entrapment. Upon his rescue, Breen gave his diary to George McKinstry, Sheriff and Inspector at Sutter’s Fort. McKinstry had himself traveled the Hastings Cut-off and arrived at Sutter’s Fort on October 19. McKinstry sent the diary to the California Star, which published in an abridged form on May 22, 1847. The diary has been more correctly transcribed, and published, by George Stewart in Ordeal by Hunger, Dale Morgan in Overland in 1846 and Joseph King in Winter of Entrapment. It is available online in original manuscript at the University of California, Berkeley, Bancroft Library.

Tuesday, December 1, 1846

December 1st Tuesday Still Snowing wind W snow about 5 1/2 feet or 6 feet deep difficult to get wood. no going from the house Commenced, our cattle all Killed buyt three or four of them, the horses and Stantons mule gone & Cattle suppose lost in the Snow no hope of finding them alive

Wednesday, December 2, 1846

wedns. 2nd Continues to snow wind W sun shineing hazily thro the clouds dont snow quite as fast as it has done snow must be over six feet deep bad fire this morning

Thursday, December 3, 1846

Thur.sd 3rd Snowed a little last night bright and Cloudy at intervals all night, to day Cloudy snows none wind S. W warm but not enough so to thaw a little today The forgoing written in the morning it immediately turned in to snow & continued to snow all day & likely to do so all night

Friday, December 4, 1846

Friday 4th Cloudy that is flying clouds neither snow or rain this day it is a relief to have one fine day, wind E by N no sign of thaw freezing pretty hard snow deep

Saturday, December 5, 1846

Saturday 5th fine clear day, beautiful sunshine thawing a little looks delightful after the long snow & storm

Sunday, December 6, 1846

Sund 6th the morning fine & Clear now some Cloudy wind S-E not much in the sunshine, Stanton & Graves manufacturing snow shoes for another mountain scrabble no account of mules

William C. Graves, son of Franklin Ward Graves, wrote in his article Crossing the Plains in ’46

published in the Russian River Flag in April and May, 1877: My father was the only man in the company who had ever seen snow shoes; and upon his return, [from the attempt of November 21-23] made fifteen pairs.

Monday, December 7, 1846

Mond. beautiful clear day wind E by S looks as if we might some fair weather no thaw

Tuesday, December 8, 1846

Tues 6th fine weather Clear & pleasant froze hard last night wind S.E. deep snow the people not stirring rong much hard work to wood sufficient to keep us warm & cook our beef

Wednesday, December 9, 1846

wedns. 9th Commenced snowing about 11 Oclock wind N.W Snows fast took in Spitzer yesterday so weak that he cannot live without help caused by starveation all in good health some having scant supply of beef Stanton trying to make a raise of some for his Indians & Self not likely to get much

Charles Stanton wrote a letter, addressed to Capt. George Donner, Donners Ville.

The letter read:

9th Dec 1846

Mrs Donner

You will please send me 1# your best tobacco. The storm prevented us from getting over the mountains we are now getting snow shoes ready to go on foot I should like to get your pocket compass as the snow is so very deep & in the event of a storm it would be invaluable Milt & Mr Graves are coming right back and either can bring it back to you The mules are all strayed off--If any should come round your camp--let some of our Company know it the first opportunity

Yours Very Respectfully

C.T. Stanton

Thursday, December 10, 1846

Thursd. 10th Snowed fast last night with heavy squalls of wind Continues still to snow the sun peeping through the clouds once in about three hours very difficult to get wood to day now about 2 Oclock looks likely to continue snowing dont know the debth of the snow may be 7 feet

Friday, December 11, 1846

11th Snowing a little wind W sun visible at times not freezing

Saturday, December 12, 1846

Satd. 12th Continues to Snow wind W weather mild freezing little

Sunday, December 13, 1846

Sunday 13th Snows faster than any previous day wind N.W. Stanton & Graves with Several others makeing preperations to cross the Mountains On Snow shoes, snow 8 feet deep on the level dull

McGlashan recounts the making of the snowshoes:

Mr. F.W. Graves was a native of Vermont, and his boyhood days had been spent in sight of the Green Mountains. Somewhat accustomed to snow, and to pioneer customs, Mr. Graves was the only member of the party who understood how to construct snow-shoes. ... By carefully sawing the ox-bows into strips, so as to preserve their curved form, Mr. Graves, by means of rawhide thongs, prepared very serviceable snow-shoes.

Monday, December 14, 1846

monday 14 fine morning sunshine cleared off last night about 12 Oclock wind E.S.E. dont thaw much but fair for a continuance of fair weather

Tuesday, December 15, 1846

Tuesday 15th still Continues fine W.S.W

In her 1891 article Across the Plains in the Donner Party

in Century Magazine, Virginia Reed wrote: Baylis Williams, who had been in delicate health before we left Springfield, was the first to die; he passed away before starvation had really set in.

Wednesday, December 16, 1846

wed’d 16th fair & pleasant froeze hard last night & the Company started on snow shoes to cross the mountains wind S-E looks pleasant

There are three detailed accounts of the snowshoe party:

- James Reed included

a synopsis of the journal of Wm. H. Eddy

in notes he provided to J.H. Merryman for the articleOf a Company of Emigrants in the Mountains of California

printed in the Illinois Journal on December 9, 1847. - John Sinclair, Alcalde of Northern California wrote a statement in February, 1847, based on

several conversations

with the survivors andfrom a few notes handed me by W. H. Eddy....

Sinclair’s statement was first published in Edwin Bryant’s What I Saw in California (1848). - J. Quinn Thornton used Eddy’s notes and Breen’s diary, supplemented by interviews, to write Oregon and California in 1848 (1849).

The accounts differ somewhat, with Thornton differing the most from the other two. I include the Reed and Sinclair versions for each day, supplemented by details from Thornton and other sources.

| Reed | Sinclair |

|---|---|

| Dec 16, 1846.--Started from the cabins, in all, fifteen persons, (the names of the persons were as follows: Mr. Graves, Patrick Dolen, Jay Fosdick, C.F. Stanton, Antonio, a Mexican, Lemuel Murphy, Lewis and Salvadore, Indians, Wm. H. Eddy, Wm. Foster, Mrs. McCutchem, Mrs. Fosdick, Miss Mary Graves, Mrs. Foster and Mrss Pike,) on snow shoes, for the California settlements;--traveled four miles, and arrived at the head of Truckey’s lake. | On the sixteenth of December, expecting that they would be able to reach the settlements in ten days, Messrs. Graves, Fosdick, Dolan, Foster, Eddy, Stanton, L. Murphy, (aged thirteen,) Antonio, a New Mexican; with Mrs. Fosdick, Mrs. Foster, Mrs. Pike, Mrs. McCutcheon, and Miss M. Graves, and the two Indians before mentioned, having prepared themselves with snow-shoes, again started on their perilous undertaking, determined to succeed or perish. Those who have ever made an attempt to walk with snow-shoes will be able to realize the difficulty they experienced. On first starting, the snow being so light and loose, even with their snow-shoes, they sank twelve inches at every step; however, they succeeded in traveling about four miles that day. |

Thornton described their departure:

The night previous to their departure was exceedingly cold. Their friends were in a state of extreme suffering and want. The hollow cheek, the wasted form, and the deep sunken eyes of his wife, Mr. Eddy told me he should never forget.Oh,said he,the bitter anguish of my wrung and agonized spirit, when I turned away from her; and yet no tear would flow to relieve my suffering.... Charles Burger was missed, and it was supposed that he had gone back. They struggled on until night, and encamped at the head of Truckee lake, about four miles from the mountain.

Donner Lake and Pass, photographed 2022

On May 22d, 1847, twenty year old Mary Graves wrote a letter to Levi Fosdick, the father of her brother-in-law Jay Fosdick:

On the 16th of December 15 of us had snow shoes prepared; and we started with 8 pounds poor beef each, to endeavor to cross the mountains to reach the settlement, and procure assistance. The distance was 150 miles.

Mary Murphy, who was thirteen at the time, gave an account several years later, which was compiled years later by Mr. S. Hunt of Marysville:

A few weeks later Mr. Graves came to our place to talk with Mother. I remember him saying,I’ve just finished making seventeen pairs of snowshoes out of wagon bows and oxhide. If the strongest set out on foot, we could make it. That will leave what food there is left for the children and the weaker company members. Are there any in your cabin, Mrs. Murphy, that want to go? It is our only choice.Of the eight of us in the cabin, Mother, who was going blind and needed attention, nevertheless dispatched Sarah, Harriet and Lemuel, leaving us babies as well as Mr. McCutcheon’s child, for she was going to join the party.

On February 9, 1896, William Murphy gave a lecture at Truckee, as reported in the Marysville Appeal:

History states how the Forlorn Hope Party started to find the way across the mountains, after several great snow storms; how I started with them, making sixteen souls, besides another who came back and how I could not keep on top of the snow without snowshoes. They thought that as I was so small and light, I could walk in their snow shoe tracks. It soon became manifest that I could not, so I went back.

Thirteen year old Virginia Reed wrote a letter on May 16, 1847 to her cousin Mary:

it would snow 10 days before it would stop thay wated tell it stoped & started again I was a goieng with them & I took sick & could not go on--thare was 15 started

Thursday, December 17, 1846

Thursd. 17th Pleasant sunshine today wind about S-E bill Murp returned from the Mountain party last evening Bealis died last night before last Milt. & Noah went to Donnor 8 days since not returned yet, thinks they got lost in the snow J Denton here today

MiltElliott. Noah James was one of the Donners’ teamsters.

Sinclair’s statement of February, 1847, included the snowshoe party’s account of the missing Milt Elliot and Noah James, and of the Donners at Alder Creek:

During the interval between this last attempt and the next, there came on a storm, and the snow fell to a depth of eight feet. In the midst of the storm, two young men started to go to another party of emigrants, (twenty-four in number,) distant about eight miles, who it was known at the commencement of the storm, had no cabins built, neither had they killed their cattle, as they still had hopes of being able to cross the mountains. As the two young men never returned, it is supposed they perished in the storm; and it is the opinion of those who have arrived here, that the party to whom they were going must have all perished.

| Reed | Sinclair |

|---|---|

| 17th.--Crossed the great chain. | On the seventeenth they crossed the divide, with considerable difficulty and fatigue, making about five miles, the snow on the divide being twelve feet deep. |

Thornton wrote: The day following they resumed their painful and distressing journey; and after traveling all day, encamped on the west side of the main chain of the Sierra Nevada, about six miles from their last camp. They were without tents.

Sinclair’s five miles or Thornton’s six miles would have brought the snowshoers to the west end of Summit Valley. More likely after ascending 1,200 feet of deep snow and crossing the divide they camped in the east end of the valley, a distance of three miles.

In about 1880, Mary Graves wrote a letter to C.F. McGlashan describing this day:

We had a very slavish day’s travel, climbing to the divide. Nothing of interest occurred until reaching the summit. The scenery was too grand for me to pass without notice, the changes being so great; walking now on the loose snow, and now stepping on a hard, slick rock a number of hundred yards in length. Being a little in the rear of the party, I had a chance to observe the company ahead, trudging along with packs on their backs. It reminded me of some Norwegian fur company among the icebergs. My shoes were ox-bows, split in two, and rawhide strings woven in, something in form of the old-fashioned, split-bottom chairs. Our clothes were of the bloomer costume, and generally were made of flannel. Well do I remember a remark of one of the company made here, that we were about as near heaven as we could get. We camped a little on the west side of the summit the second night.

The final climb to Donner Pass, photographed 1998

The Top of Donner Pass, photographed 1998

View West from Top of the Pass, photographed 1997

Friday, December 18, 1846

Fridd. 18 beautiful day sky Clear it would be delightful were it not for the snow lying so deep thaws but little on the south side of shanty saw no strangers today from any of the shantys

| Reed | Sinclair |

|---|---|

| 18th.--Descended Juba creek about six miles; commenced snowing; wind blowing cold and furiously. | The next day they made six miles, |

Thornton’s account: On the 18th they traveled five miles, and encamped. Mr. Stanton became snow-blind during the day, and fell back, but came up after they had been in camp an hour.

Six miles would have brought the snowshoers through Summit Valley, south of present Old Highway 40, and along the ridge to present Cascade Lake. Today this section of the Emigrant Trail is part of the Royal Gorge Cross Country Ski Area, and the groomed trail is still called Emigrant Trail. It leads from the upper end of Summit Valley across Soda Springs Road and along the County Road to a warming hut just above Cascade Lake.

Emigrant Road West of Summit Valley, photographed 1998

Saturday, December 19, 1846

Sa.td 19 Snowd last night commenced about 11 Oclock Squalls of wind with snow at intervals this morning thawing wind N. by W alittle Singular for a thaw may Continue, it Continues to Snow Sun Shining cleared off Towards evening

| Reed | Sinclair |

|---|---|

| 19th.--Storm continued; feet commenced freezing. | ... and, on the nineteenth five, it having snowed all day. |

Thornton’s account: December 19.--Although the wind was from the northwest, yet the snow which had fallen the previous night, thawed alittle. Mr. Stanton again fell behind, in consequence of blindness. He came up an hour after they were encamped.

Five miles would have brought the snowshoers down the slope from present Cascade Lake to the Yuba River at Donner Trail School (west of Kingvale), and along the Yuba Bottoms to present Hampshire Rocks campground.

Descent to Big Bend of the Yuba, and Tree Scarred from Ropes, photographed 1999

Emigrant Road at Big Bend on the Yuba River, photographed 1996

Sunday, December 20, 1846

Sund.20 night clear froze alittle now clear & pleasant wind N W thawing alittle Mrs Reid here. no account of Milt yet Dutch Charley started for Donnghs turned back not able to proceed tough times, but not discouraged our hopes are in God Amen

[Dutch Charley was Karl Burger the Keseberg’s teamster.]

| Reed | Sinclair |

|---|---|

| 20th.--Left Juba; traveled four miles. | On the twentieth the sun rose clear and beautiful, and cheered by its sparkling rays, they pursued their weary way. From the first day, Mr. Stanton, it appears, could not keep up with them, but had always reached their camp by the time they got their fire built, and preparations made for passing the night. This day they had travelled eight miles, and encamped early; and as the shades of evening gathered round them, many an anxious glance was cast back through the deepening gloom for Stanton; but he came not. |

Sinclair’s eight miles would have brought the snowshoers down the Yuba River past Cisco Butte, where the Trail left the river and ascended to the south side of a peak overlooking the river (shown as point 6241’ on the USGS topo map), and past present Crystal Lake to Sixmile Valley. The mileages may be reconciled if Reed’s four miles is taken as the miles after leaving the Yuba. A more important discrepancy is that Reed does not record Stanton’s disappearance until the next day.

Thornton agrees with Reed about Stanton:

The wind on the 20th was from the northeast. In the morning they resumed their journey, and guided by the sun, as they had hitherto been, they traveled until night. Mr. Stanton again fell behind.

Thornton’s statement that they were guided by the sun suggests that Stanton’s letter of December 9 to the Donners was carried by the missing Milt Elliott and Noah James. In the letter Stanton asked to borrow a compass, which likely was with the missing men.

Today, the trail past Crytstal Lake is part of the NACO West campground trail system south of Yuba Gap. The trail to the camp in Sixmile Valley is part of the Eagle Mountain Nordic cross-country trail system. At Cascade Lake, nine miles east of Sixmile Valley, a sign states that Charles Stanton’s grave is nearby, but this is incorrect. According to all three versions of the snowshoe party, Stanton camped with the party along the Bottoms of the Yuba River which is past Cascade Lake.

Looking East up Sixmile Valley, photographed 1996

Monday, December 21, 1846

Mon 21 Milt got back last night from Donos camp sad news Jake Donno Sam Shoemaker Rinehart & Smith are dead the rest of them in a low situation snowed all night with a strong S-W wind to day Cloudy wind Continues but not Snowing, thawing sun Shineing dimly in hopes it will clear off

Thornton’s Oregon and California in 1848 contains this interesting statement:

I was informed by Mr. Eddy that George Donner, with whom Rianhard subsequently traveled, told him that Wolfinger had not died as stated--that this fact he learned from a confession made by Rianhard a short time previous to his death; and that he would make the facts public as soon as he arrived in the settlements

This statement raises questions about when Eddy heard the facts from George Donner as reported by Thornton. Eddy had left with the snowshoers on the 16th, five days before Milt Elliott returned to the Lake with the news of Reinhart’s death at the Donner camp on Alder Creek, so it is doubtful Eddy heard anything about Reinhart then. Eddy did not return to the camps until he returned with the Third Relief on March 13, mere weeks before George Donner’s death. From the accounts of the Third Relief it is not clear if they even visited the Donner camp. Although Eddy spoke with Mrs. Donner, he may have spoken with her at the Lake cabins as she had stated her intent to visit her children.. Even if Eddy visited the Donner camp, George Donner would have been in a very weak condition, possibly too weak to relate the details of Reinhart’s confession.

| Reed | Sinclair |

|---|---|

| 21st.--Went down the mountain in a southerly direction; provisions exhausted; Stanton snow blind; he did not reach camp at night | Before morning the weather became stormy, and at daylight they started and went about four miles, when they encamped, and agreed to wait and see if Stanton would come up; but that night his place was again vacant by their cheerless fire, while he, I suppose, had escaped from all further suffering, and lay wrapped in his ’winding sheet of snow’--’His weary wand’rings and his travels o’er.’ |

Mary Graves told a story about Stanton not following the party, as reported by Eliza Farnham in California In-Doors and Out, published in 1856:

On the morning of the fifth day out, poor Stanton sat late by the camp-fire. The party had set off, all but Miss G., and as she turned to follow her father and sister, she asked him if he would soon come. He replied that he should, and she left him smoking. He never left the desolate fireside.

Thornton appears to have added two days to the journey:

The wind next day changed to southwest, and the snow fell all day. They encamped at sunset, and about dark Mr. Stanton came up. They resumed their journey on the 22d. Mr. Stanton came into camp in about an hour, as usual. That night they consumed the last of their little stock of provisions. They had limited themselves to one ounce at each meal, since leaving the mountain camp, and now the last was gone. They had one gun, but they had not seen a living creature. ...

December 23.--During this day Mr. Eddy examined a little bag for the purpose of throwing out something, with a view to getting along with more ease. In doing this, he found about half a pound of bear’s meat, to which was attached a paper upon which his wife had written in pencil, a note signedYour own dear Eleanorin which she requested him to save it for the last extremity, and expressed the opinion that it would be the means of saving his life. ... On the morning of this day Mr. Stanton remained at the camp-fire, smoking his pipe. He requested them to go on, saying that he would overtake them. The snow was about fifteen feet deep. Mr. Stanton did not come up with them.

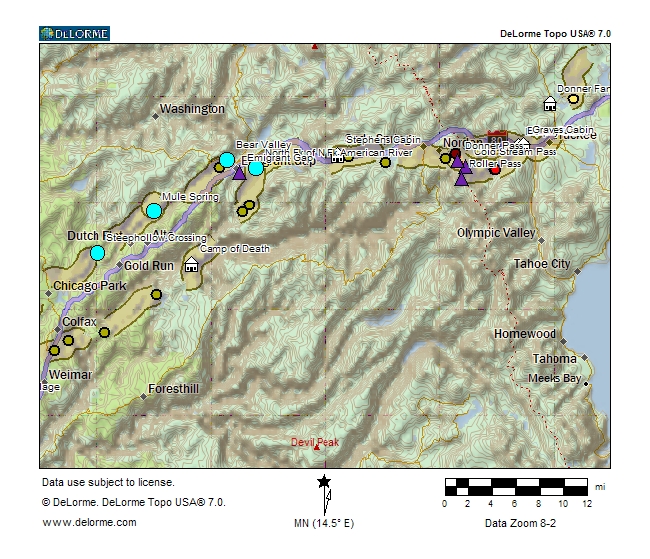

From the west end of Sixmile Valley, the Trail descended almost due west to a small valley below a low spot on a ridge, Emigrant Gap. The ridge separates the American River drainage (on the southeast) from the Bear River drainage (on the northwest). A short climb to the Gap would have brought the Snowshoe Party to the obvious 700’ descent into Bear Valley. As noted by Reed, they did not keep to the west but turned south, towards the North Fork of the American River. They most likely followed the North Fork of the North Fork of the American River and camped in or near present Onion Valley.

Trail from Sixmile Valley to Emigrant Gap, photographed 1996

Wrong Turn to the North Fork of the North Fork of the American River, photographed 1996

Onion Valley, photographed 1997

The route of the Snowshoe Party is the subject of great debate, in part because the creeks draining into the North Fork of the American River run through steep narrow canyons that are nearly impassable. Daniel James Brown, author of The Indifferent Stars Above, thinks the Snowshoe Party didn’t turn south at the North Fork of the North Fork, instead turning south after reaching Emigrant Gap but missing the descent to Bear Valley. If so, they would have stayed on the divide between the Bear River and the American River. This divide was the route taken by John Fremont to reach Sutter’s Fort when he crossed the Sierra in late 1845. It is the route of present I-80. It seems unlikely that the Snowshoe Party, who were heading southwest to Johnson's Ranch, would leave the divide at Fulda Creek, Blue Canyon or Green Valley to descend south into the steep American River canyon. It is more likely that after making a wrong turn they followed the easiest route southwesterly unless forced to turn by difficult ground. From Sixmile Valley the easiest ground lies south towards Onion Valley.

Tuesday, December 22, 1846

Tue.sd 22nd Snowd all last night Continued to Snow all day with Some few intermissiones had a Severe fit of the gravel yesterday I am well to day, Praise be to the God of Heaven

| Reed | Sinclair |

|---|---|

| 22d.--Remained in camp waiting for Stanton. | On the twenty-second the storm still continued, and they remained in camp until the twenty-third, |

Thornton wrote that

they resumed their melancholy journey, and after traveling about a mile, they encamped to wait for their companion. They had nothing to eat during the day. Mr. Stanton did not come up. The snow fell all night, and increased one foot in depth. They now gave up poor Stanton for dead.

Wednesday, December 23, 1846

wen. 23d Snowd alittle last night clear to day & thawing alittle, Milt took some of his meat to day all well at their Camp began this day to read the Thirty days prayer, may Almighty God grant the request of an unworthy Sinner that I am. Amen

| Reed | Sinclair |

|---|---|

| 23d.--Cleared off; ascended a mountain for observation; still in hopes that Stanton would arrive. | the twenty-third, when they again started, although the storm still continued, and traveled eight miles. They encamped in a deep valley. Here the appearance of the country was so different from what it had been represented to them, (probably by Mr. Stanton,) that they came to the conclusion that they were lost; and the two Indians on whom they had placed all their confidence, were bewildered. |

From Onion Valley the North Fork of the North Fork runs on the west side of 5,300’ Scott Peak and the East Fork runs east of Scott Peak along the north side of 5,600’ Texas Hill. If Reed’s account is correct, the Snowshoe Party probably ascended Texas Hill for observation. If Sinclair is correct they probably descended into Willmont Canyon south of Texas Hill.

Sinclair’s account continues:

In this melancholy situation they consulted together, and concluded they would go on, trusting in Providence, rather than return to their miserable cabins. They were, also, at this time out of provisions, and partly agreed, with the exception of Mr. Foster, that in case of necessity, they would cast lots who should die to preserve the remainder. During the whole of the night it rained and snowed very heavily, ...

In her letter of May 22, 1847, Mary Graves wrote

We made good progress until the 8th day, when we got lost. It commenced raining and continued until the next day at night--then commenced snowing and continued three days and nights.

According to Mary Graves, as reported by Eliza Farnham in California In-Doors and Out, published in 1856:

So, on the evening of the seventh day, when they had given up all expectation of seeing their guide, and would scarcely have lifted a hand or foot to escape from death, a violent rain set in. There was then no possibility of kindling a fire to warm their shivering frames. The pitiless flood drenched, in a short time, their tattered garments. They laid their aching bones upon the oozing snow, and wore away a night which inflicted the agonies of a hundred deaths upon them.

Thursday, December 24, 1846

Thur.sd it rained all night & still continues to rain poor prospect for any kind of Comfort Spiritual or temporal, wind S; may God help us to spend the Christmass as we ought considering circumstances

| Reed | Sinclair |

|---|---|

| 24th--Left top of mountain; proceeded down a valley three miles; storm recommenced with greater fury; extinguished fires. | and by morning the snow had so increased that they could not travel; while to add to their sufferings, their fire had been put out by the rain, and all their endeavors to light another proved abortive. ... Antonio died about nine, A.M.; and at eleven o’clock, P.M., Mr. Graves. |

Reed’s three miles from the mountain would have brought the Snowshoe Party to Willmont Canyon south of Texas Hill.

Sinclair continues:

In this critical situation, the presence of mind of Mr. Eddy suggested a plan for keeping themselves warm, which is common amongst the trappers of the Rocky Mountains, when caught in the snow without fire. It is simply to spread a blanket on the snow, when the party, (if small,) with the exception of one, sit down upon it in a circle, closely as possible, their feet piled over one another in the centre, room being left for the person who has to complete the arrangement. As many blankets as necessary are then spread over the heads of the party, the ends being kept down by billets of wood or snow. After everything is completed, the person outside takes his place in the circle. As the snow falls it closes up the pores of the blankets, while the breath from the party underneath soon causes a comfortable warmth. It was with a great deal of difficulty that Mr. Eddy succeeded in getting them to adopt this simple plan, which undoubtedly was the means of saving their lives at this time. In this situation they remained thirty-six hours.

According to Mary Graves, as reported by Eliza Farnham in California In-Doors and Out, published in 1856:

The morning came, and still the flood fell. They roused themselves to move on a little, if it were possible, despite the storm; but they had lost their course, and the sun no longer befriended them. It was proposed to return to the cabins, following their own tracks, but the Indians would not consent, and Miss G. resolutely determined to follow them. There was nothing possible, there, but starvation. The fate before them could not be worse, and might be better. Miss G.’s resolution encouraged her companions. They went on all day without a morsel of food, the rain pouring continuously. At night it ceased. Some were confused in their perceptions, some delirious, some raving. Those who were strong enough to realize their condition, might well now despair. The women bore up better than the men. One of them had a cape or mantle stuffed with raw cotton, and upon a minute examination of it, she found, between the shoulders, about an inch square of the inner surface dry. The lining was cut, and enough taken out to catch the spark from the flint. They lost or left their axe, but were able to make a fire, after much difficulty, of a few gathered boughs. They sat down around it. There was nothing else to be done.

Thornton wrote that:

the painful journey was again continued, and after traveling two or three miles, the wind changed to the south-west. The snow beginning to fall, they all sat down to hold a council for the purpose of determining whether to proceed. All the men but Mr. Eddy refused to go forward. The women and Mr. Eddy de-clared they would go through or perish. Many reasons were urged for returning, and among others the fact that they had not tasted food for two days, and this after having been on an allowance of one ounce per meal. It was said that they must all perish for want of food. At length, Patrick Dolan proposed that they should cast lots to see who should die, to furnish food for those who survived. Mr. Eddy seconded the motion. William Foster opposed the measure. Mr. Eddy then proposed that two persons should take each a six-shooter, and fight until one or both were slain. This, too, was objected to. Mr. Eddy at length proposed that they should resume their journey, and travel on till some one died. This was finally agreed to, and they staggered on for about three miles, when they encamped. They had a small hatchet with them, and after a great deal of difficulty they succeeded in making a large fire. About 10 o’clock on Christmas night, a most dreadful storm of wind, snow, and hail, began to pour down upon their defenseless heads. While procuring wood for the fire, the hatchet, as if to add another drop of bitterness to a cup already overflowing, flew from the handle, and was lost in unfathomable snows. About 11 o’clock that memorable night, the storm increased to a perfect tornado, and in an instant blew away every spark of fire. Antoine perished a little before this from fatigue, frost, and hunger. The company, except Mr. Eddy and one or two others, were now engaged in alternatingly imploring God for mercy and relief. That night’s bitter cries, anguish, and despair, never can be forgotten. Mr. Eddy besought his companions to get down upon blankets, and he would cover them up with other blankets; urging that the falling snow would soon cover them, and they could thus keep warm. In about two hours this was done. Before this, however, Mr. Graves was relieved by death from the honors of that night. Mr. Eddy told him that he was dying. He replied that he did not care, and soon expired.

Friday, December 25, 1846

Friday 25th began to snow yesterday about 12 Oclock snowd all night & snows yet rapidly wind about E by N Great difficulty in getting wood John & Edwd has to get I am not able Offerd, our prayers to God this Cherimass morning the prospect is apalling but hope in God amen

Virginia Reed, in her 1891 article in Century Magazine, remembered that Christmas:

Christmas was near, but to the starving its memory gave no comfort. It came and passed without observance, but my mother had determined weeks before that her children should have a treat on this one day. She had laid away a few dried apples, some beans, a bit of tripe, and a small piece of bacon. When this hoarded store was brought out, the delight of the little ones knew no bounds. The cooking was watched carefully, and when we sat down to our Christmas dinner mother said,Children, eat slowly for this one day you can have all you wish.So bitter was the misery relieved by that one bright day, that I have never since sat down to a Christmas dinner without my thoughts going back to Donner Lake.

Mary Murphy, who was thirteen at the time, gave an account many years later to Mr. S. Hunt of Marysville:

Christmas we had a meal of boiled bones and oxtail soup. After supper Mother was barely able to put the babies to bed, and later on that evening with brother William reading her favorite psalm from the Good Book, she became bedridden and seriously ill.

| Reed | Sinclair |

|---|---|

| 25th.--Antonio and Mr. Graves died; remained in camp. | On the twenty-fifth, about four o’clock, P.M. Patrick Dolan died; he had been for some hours delirious, and escaped from under their shelter, when he stripped off his coat, hat and boots, and exposed himself to the storm. Mr. Eddy tried to force him back, but his strength was unequal to the task. He, however, afterward returned of his own accord,and laid down outside their shelter, when the succeeded in dragging him inside. |

In her letter of May 22, 1847, Mary Graves wrote: Father died on Christmas night at 11 o’clock in the commencement of the snow storm.

According to Mary Graves, who spoke to Eliza Farnham whose California In-Doors and Out was published in 1856:

The father, whose two daughters were of the company, was the first released. The chilling rain had pierced his emaciated frame, and subdued the energy which had resisted courageously all that had gone before. ... In that desolate hour of death, he called his youngest daughter to his side, and bade her cherish and husband every chance of life, in the fearful days which he knew awaited them. ... She must revolt at nothing that would keep life in her till she could reach some help for those whom they both loved. He clearly foreshadowed the terrible necessity to which, within a few hours, he saw they must come, and died, leaving his injunction upon her, to yield to it as resolutely as as she had done everything else that had been required of her, since their sufferings began.

Thornton wrote:

They remained under the blankets all that night, until about 10 o’clock, A.M., of the 26th, when Patrick Dolan, becoming deranged, broke away from them, and getting out into the snow, it was with great difficulty that Mr. Eddy again got him under. They held him there by force until about 4 o’clock, P.M., when he quietly and silently sunk into the arms of death. He was from Dublin, Ireland. Lemuel Murphy became deranged on the night of the 26th, and talked much about food.

Saturday, December 26, 1846

Satd, 26th Cleared off in the night today Clear & pleasant Snowd about 20 inches or two feet deep yesterday, the old snow was nearly run off before it began to snow now it is all soft the top dry & the under wet wind S E

| Reed | Sinclair |

|---|---|

| 26th.--Could not proceed; almost frozen; no fire. | On the twenty-sixth, L. Murphy died, he likewise being delirious; and was only kept under their shelter by the united strength of the party. |

Sinclair continues:

In the afternoon of this day they succeeded in getting fire into a dry pine-tree. Having been four entire days without food, and since the month of October on short allowance, there was now but two alternatives left them--either to die, or preserve life by eating the bodies of the dead; slowly and reluctantly they adopted the latter alternative.

Sunday, December 27, 1846

Sundy, 27th Continues clear froze hard last night Snow very deep say 9 feet thawing alittle in the Sun Scarce of wood to day chop a tree dow it sinks in the Snow & is hard to be got

| Reed | Sinclair |

|---|---|

| 27th.--Still in camp; no fire; Patrick Dolin died. | On the twenty-seventh they took the flesh from the bodies of the dead; and on that, and the two following days they remained in camp drying the meat, and preparing to pursue their journey. |

Thornton adds:

On the morning of the 27th, Mr. Eddy blew up a powder-horn, in an effort to strike fire under the blankets. His face and hands were much burned. Mrs. McCutcheon and Mrs. Foster were also burned, but not seriously. About 4 o’clock, P.M., the storm died away, and the angry clouds passed off. Mr. Eddy immediately got out from under the blankets, and in a short time succeeded in getting fire into a large pine tree. His unhappy companions then got out; and having broken off boughs, they put them before the fire. The flame ascended to the top of the tree, and burned off great numbers of dead limbs; some of them as large as a man’s body; but such was their weakness and indifference, that they did not seek to avoid them at all. Although the limbs fell thick, they did not strike.

Monday, December 28, 1846

Monday 28th Snowd. last night cleared off this morning snowd. alittle now Clear & Pleasant

In 1891, Virginia Reed wrote:

During the closing days of December, 1846, gold was found in my mother’s cabin at Donner Lake by John Denton. I remember the night well. The storm fiends were shrieking in their wild mirth, we were sitting about the fire in our little dark home, busty with our thoughts. Denton with his cane kept knocking pieces off the large rocks used as fire-irons on which to place the wood. Something bright attracted his attention, and picking up pieces of the rock he examined them closely; then turning to my mother he said:Mrs. Reed, this is gold.My mother replied that she wished it were bread. Denton knocked more chips from the rocks, and he hunted in the ashes for the shining particles until he had gathered about a teaspoonful. This he tied in a small piece of buckskin and placed in his pocket saying,If we ever get away from here I am coming back for more.

| Reed | Sinclair |

|---|---|

| 28th.--Storm abated; succeeded in making fire; Lemuel Murphy died." | they remained in camp drying the meat, and preparing to pursue their journey. |

Tuesday, December 29, 1846

Tuesday 29th fine clear day froze hard last night. Charley sick. Keysburg has Wolfings Rifle gun

Charley

was Charles Berger (or Karl Burger), the Keseberg’s teamster. Breen’s reference to Keseberg having Wolfinger’s rifle could be an indication that some of the party suspected foul play in Wolfinger’s death.

| Reed | Sinclair |

|---|---|

| 29th.--Nor food for five days; a portion of the company eat human flesh. | they remained in camp drying the meat, and preparing to pursue their journey. |

Wednesday, December 30, 1846

Weds.d 30th fine clear morning froze hard last night Charley died last night about 10 Oclock had with him in money $1.50 two good loking selver watches one razor 3 boxes caps Keysburg tok them into his possession Spitzer took his coat & waistcoat Keysburg all his other little effects Gold pin one shirt and tools for shaveing.

[Charley

was Charles Berger (or Karl Burger), the Keseberg’s teamster.]

| Reed | Sinclair |

|---|---|

| 30th.--Stripped all the flesh from three of the bodies; traveled four miles. | On the thirtieth they left this melancholy spot, where so many of their friends and relatives had perished; and with heavy hearts and dark forbodings of the future, pursued their pathless course through the new-fallen snow, and made about five miles; |

Sinclair quotes Eddy as calling the camp this melancholy spot.

According to Thornton, To this place they gave the name of ‘The Camp of Death.’

Four or five miles travel down the North Fork of the North Fork from The Camp of Death

would have brought the party to about 2,600’ at the bottom of a steep canyon. Most likely they traveled on Sawtooth Ridge which rises to about 4,500 feet on the southeast side of the canyon.

In her letter of May 22, 1847, Mary Graves wrote: During the storm we had neither fire nor food. When it was over we started (leaving 4 of our number there.)

Thornton describes the day:

On the morning of December 30th they resumed their journey, their feet being so swollen that they had burst open, and, although they were wrapped in rags and pieces of blankets, yet it was with great pain and difficulty that they made any progress.

Thursday, December 31, 1846

Thursday 31th last of the year may we with Gods help spend the Comeing year better than the past which we purpose to do if Almighty God will deliver us from our present dredful situation which is our prayer if the will of God sees it fitting for us Amen morning fair now Cloudy wind E by S for three days past freezing hard every night looks like another snow storm snow storms are dredful to us, snow very deep Crust on the snow

| Reed | Sinclair |

|---|---|

| 31st.---Traveled six miles. | next day about six miles. |

Thornton gives the date for the first day of travel from The Camp of Death

as December 30th, and recounts only one travel day. He says

They encamped, late in the afternoon, upon the high bank of a very deep canon. From this point they could distinctly see a valley which they believed to be the valley of the Sacramento.

As veriifed by the Forlorn Hope Expedition, from some points on Sawtooth ridge it is possible to see the Sacramento Valley to the west.