August, 1846

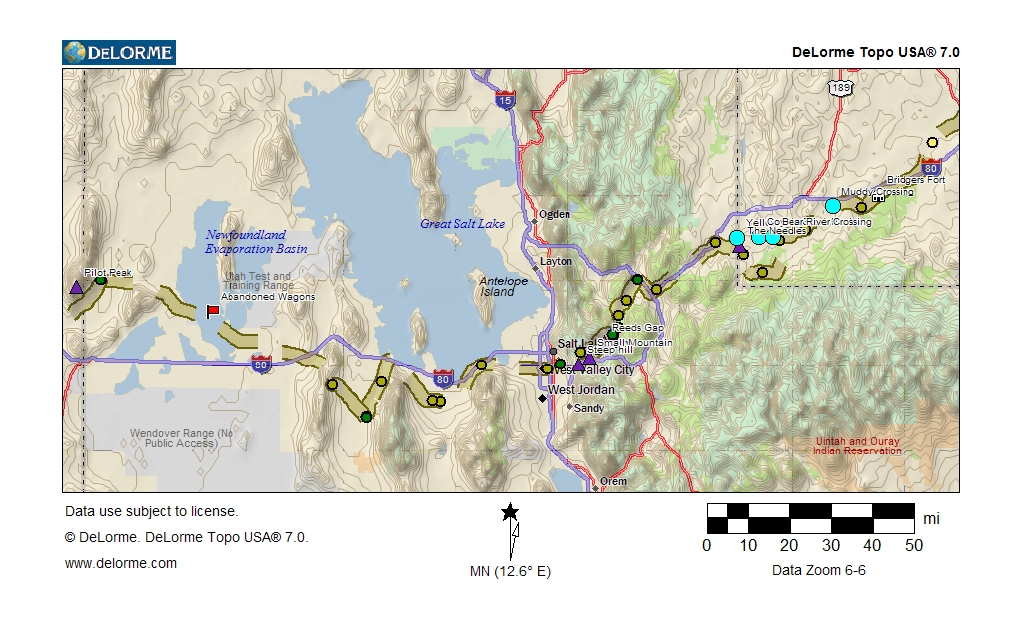

The Donner Party traveled from Bridger’s Fort (in what is now southwestern Wyoming) to the salt desert south and west of Salt Lake (near the present Utah-Nevada border).

The dated entries below are from the diary of Hiram Miller and James F. Reed. The Diary is controversial to some historians. The existence of the diary was not known until the estate of Martha (Patty) Reed donated it to Sutter’s Fort Historical Museum in 1945. Apparently neither Virginia nor Patty revealed the diary to McGlashan. Virginia apparently did not use it as a source for her Century Magazine article in 1891. Some of the entries appear to have been written after the events, which led both Stewart and King to question it. King went so far as to suggest that some entries may have been written after Reed arrived in California.

Saturday, August 1, 1846

Sat 1 Augt 1846--left Camp this morning early and passed through Sevral Valleys well watered with plenty of grass, and encamped at the head of Iron Spring Vally making 15

[The camp is now known as Pioneer Hollow above Spring Valley.]

Sunday, August 2, 1846

Sond 2 this morning left Camp late on acct of an ox being missing Crossed over a high ridge or mountain with tolerable rough road and encamped on Bear river making 16 on a little Creek abut 4 miles from Bear River we ought to have turned to the right and reached Bear River in one mile Much better road Said to be

The Donners followed the route taken by the Harlan-Young wagons, across the Altamont Divide into the Sulphur Creek drainage (Hilliard Flat), and continued southwesterly over a ridge to the Bear River near Mill Creek. Hastings was ahead scouting, and returned with directions for the Hoppe Party, including the diarist Heinrich Lienhard. Lienhard recorded that, based on Hasting’s advice, they crossed the ridge west of Sulphur Creek and headed directly to the Bear river. Reed’s comment that this turn to the right

was said

to be a better road suggests that Reed wrote this entry many days later, after he had scouted ahead and caught up to Hastings and the other wagons.

Monday, August 3, 1846

Mon 3 left our encampment and traveled a tolerable rough Road Crossing Several Very high hills and encamped at the head of a larger Vally with a fine little runing Stream passing by the edge of our Camp Cattle plenty of grass County appear more hale west Made this day 16,

[This little stream was probably upper Yellow Creek.]

On this day, Charles Stanton added a last note to his letter of July 19:

Bear River, August 3, 1846 .... I may not have another opportunity of sending you letters till I reach California; .... We take a new route to California, never traveled before this season; consequently our route is over a new an interesting region. We are now in the Bear river valley, in the midst of the Bear River mountains, the summits of which are covered with snow. As I am now writing, we are cheered by a warm summer’s sun, while but a few miles off, the snow covered mountains are glittering in its beams.

From the trail west of the Bear River, the emigrants could see the Uinta mountains 30 miles to the south, with summits up to 13,000 feet. Stanton’s letter raises another mystery of the Donner Party: Who carried this letter back to Bridger’s Fort and the States? In his other letters, Stanton mentions the carrier, but this letter is silent. Perhaps the answer lies in a story recounted by Virginia Reed in a letter to McGlashan, and by Harry J. Breen, son of Edward Breen, told to him by his father:

I must relate an incident that my father say told happened to him when the party was not far west of Fort Bridger. He says that Patty Reed and he were galloping along on their saddle ponies, when his horse put one or both front feet into a badger or prairie dog burrow and took a hard fall. He was knocked out and when some of the others came to pick him up they found he had a compound break of his left leg between the knee and ankle. Someone was sent back to the Fort for aid in repairing the damage, and after what seemed to him a long time a rough looking man with long whiskers rode up on a mule. He examined the boy’s leg and proceeded to unroll a small bundle.... Out of this came a short saw and a long bladed knife. The boy of course set up a loud cry when he sensed what was to be done and finally after long discussion convinced his parents that he should keep his leg. The old mountain man was given five dollars and sent back to the Fort muttering to himself for not being given the chance to display his skill as a surgeon.

Meanwhile, back at the Fort, the Graves family had arrived, as recounted by William Graves in 1877 in his article in the Russian River Flag: With our three wagons we went on to Fort Bridger; here we heard of The Donner Party, some three or four days ahead of us.

Tuesday, August 4, 1846

Tus 4 this day left our encampmt about 2 oclock made this day about 8 our encamp was this day in red Run Valley fork of weaver

This camp was in the upper end of Echo Canyon, the present route of Interstate 80. From Fort Bridger to this point, Hastings’ Cut-off crosses country that is, to this day, untracked except by the barest of dirt roads. From this point west to the Great Salt Lake the Donner’s route closely parallels the present Interstate 80 and Utah Highway 65.

Photograph of Mormon Wagon Train heading East in Echo Canyon, in 1860’s

Wednesday, August 5, 1846

Weds 5 Started early and traveled the whole day in Red Run Valley and encampe below its entrans into Weavers Creek 15

[This camp was in Echo Canyon, near present Echo, Utah.]

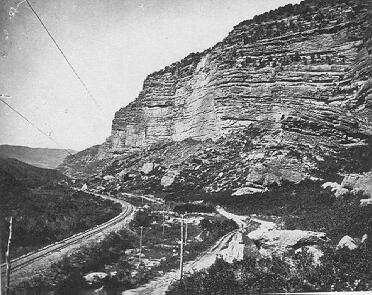

The Amphitheater, in Echo Canyon, photographed by William Jackson, 1870

The Pulpit, at the mouth of Echo Canyon, photographed by William Jackson,

1870

(This unique formation was later dynamited to make way for the railroad and

highway)

Thursday, August 6, 1846

Thus 6 left our encamp. about ten oclock and encamp above the Cannon here we turn to the left hand & Cross the Mounten instead of the Cannon which is impassible although 60 Waggons passed through this day made 10

[This camp was near present Henefer, Utah.]

After his arrival in California, James Reed wrote to his brother-in-law James Keyes, and recounted the journey of the Donner Party. On December 9, 1847, the Illinois Journal (formerly the Sangamo Journal) in Springfield published this paraphrased version:

He says that his misfortunes commenced on leaving Fort Bridger, which place he left on the 31st of August [should be July], 1846, in company with eighty-one others. Nothing of note occurred until the 6th of September [should be August], when they had reached within a few miles of Weaver Canon, where they found a note from a Mr. Hastings, who was twenty miles in advance of them, with sixty wagons, saying that if they would send for him he would put them upon a new route, which would avoid the Canon and lessen the distance to the great Salt Lake several miles. Here the company halted, and appointed three persons, who should overtake Mr. Hastings and engage him to guide them through the new route, which was promptly done.

In a letter to the California Star, Yerba Buena (San Francisco), published on February 13, 1847, George McKinstry recounted his knowledge of the Donner Party, then stranded in the Sierra Nevada mountains:

They followed on in the train until they were near theWeber River canon,and within some 4 or 5 days travel of the leading waggons, when they stopped and sent on three men, (Messrs. Reed, Stanton and Pike) to the first company, (with which I was then traveling in company,) to request Mr. Hastings to go back and show them the pack trail from the Red Fork of Weber River to the Lake.

According to Reed’s March 25, 1871 account in the Pacific Rural Press:

Leaving Fort Bridger, we unfortunately took the new route, traveling on without incident of note, until we arrived at the head of Webber canyon. A short distance before reaching this place we found a letter sticking in the top of a sage bush. It was from Hastings. He stated that if we would send a messenger after him he would return and pilot us through a route much shorter and better than the canyon. A meeting of the company was held, when it was resolved to send Messrs. McCutchen, Stanton and myself to Mr. Hastings; also we were at the same time to examine the canon and report at short notice.

Thornton in 1848, based on Eddy’s account, states that the three were Reed, Stanton and Pike. McGlashan appears to have relied on Thornton and not on Reed’s account, as did Virginia Reed in her 1891 article for Century Magazine:

We were seven days in reaching Weber Canon, and Hastings, who was guiding a party in advance of our train, left a note by the wayside warning us that the road through Weber Canon was impassable and advising us to select a road over the mountains, the outline of which he attempted to give on paper. These directions were so vague that C.T. Stanton, William Pike, and my father rode on in advance ....

Stewart accepts Reed’s account and names McCutchen as the third member.

Why did the Harlan-Young Party descend the Weber canyon? Edwin Bryant, who had crossed the Wasatch by mule, wrote in his diary on July 29:

Mr. Hudspeth and two young men came into camp early this morning, .... They had forced their way though the upper canon, and proceeded six miles further up Weber river, where they met a train of about forty emigrant wagons under the guidance of Mr. Hastings, ... The difficulties to be encountered by these emigrants by the new route will commence at that point; and they will, I fear, be serious. Mr. Hudspeth thinks that the passage through the canon is practicable, by making a road in the bed of the stream at short distances, and cutting the timber and brush in other places.

Why did Hastings lead the wagons through the Weber River canyon, but then advise the Donners to follow the pack trail? Heinrich Lienhard wrote in his journal:

on the 3rd of August as we were making our way down along the river in a northerly direction, and after we had traveled about 5 miles, we encountered Captain Hastings, who had returned to meet us. By his advice we halted here. He was of the opinion that we, like all the companies who had gone in advance of us, were taking the wrong road. He had advised the first companies that on arriving at the Weber River they should turn to the left which would bring them by a shorter route to the Salt Lake; this advice they had not followed, but by good luck they had been able to make their way down the river.

It is likely that Hastings was headed back to the canyon entrance to leave the note for the Donner Party warning them against the canyon route.

Friday, August 7, 1846

Frid 7 in Camp on weaver at the mouth of Canon

[Note that Reed wrote this entry describing the location of the wagons, although he had gone on ahead to overtake Hastings.]

Saturday, August 8, 1846

Sat 8 Still in Camp

Sunday, August 9, 1846

Sond 9 Still in Camp

On this day, Reed, Stanton and Pike (or McCutchen) caught up with Hastings at the south end of Salt Lake. Reed wrote in a letter to his brother-in-law James Keyes, paraphrased in the Illinois Journal on December 9, 1846: Mr. Hastings gave them directions concerning this road, and they immediately recommenced their journey.

Reed gave a fuller account in his 1871 article in the Pacific Rural Press:

We overtook Mr. Hastings at a place we called Blackrock, south end of Salt Lake, leaving McCutchen and Stanton here, their horses having failed. I obtained a fresh horse from the company Hastings was piloting, and started on my return to our company, with Mr. Hastings. When we arrived at about the place where Salt Lake city is built, Mr. Hastings, finding the distance greater than anticipated by him, stated that he would be compelled to return the next morning to his company. We camped this evening in a canyon.

Blackrock is probably the large rock east of Lake Point on the south shore of the lake. The party probably camped in Emigration Canyon.

As recounted by Virginia Reed in 1891:

...C.T. Stanton, William Pike, and my father rode on in advance and overtook Hastings and tried to induce him to return and guide our party. He refused, but came back over a portion of the road, and from a high mountain endeavored to point out the general course. Over this road my father traveled alone, taking notes, and blazng trees, to assist him in retracing his course, ...

Black Rock, east of Lake Point, UT, photographed 1999

Monday, August 10, 1846

Mo 10 Still in Campe James F. Reed this evening returned he and two others having been Sent by the Caravan to examine the Canon and proceed after Mr Hastings, who left a Note on the road that if we Came after him he would return and Pilot us though his new and direct Rout to the South end of the Salt Lake Reed having examined the new rout entirely and reported in favour, which induced the Company to proceed

According to Reed’s 1871 article in the Pacific Rural Press:

Next morning ascending to the summit of the mountain where we could overlook a portion of the country that lay between us and the head of the cañon, where the Donner party were camped. After he gave me the direction, Mr. Hastings and I separated. He returning to the companies he had left the morning previous, I proceeding on eastward. After descending to what may be called the table land, I took an Indian trail and blazed the route where it was necessary that the road should be made, if the company so directed when they heard the report. When McCutchen, Stanton and myself got through Webber cañon on our way to overtake Mr. Hastings, our conclusions were that many of the wagons would be destroyed in attempting to get through the canon. Mr. Stanton and McCutchen were to return to our company as fast as their horses would stand it, they having nearly given out. I reached the company in the evening and reported to them the conclusions in regard to Weber canon, at the same time stating that the route that I had blazed that day was fair, but would take considerable labor in clearing and digging. They agreed with unanimous voice to take that route if I would direct them in the road making, they working faithfully until it was completed.

Heinrich Lienhard was with Hastings, and wrote in his manuscript,

On the morning of the tenth of August ... Hastings had ridden back to show the way, if necessary, to the parties that had stayed behind. ... On the eleventh of August we remained in camp. ... We spent the twelfth of August in the same place ... Mr. Hastings had returned ....

According to the Graves family, they joined the Donner Party just as Reed had returned and recommended the new road. William Graves in his 1877 article Crossing the Plains in ’46

:

He [Hastings] showed him [Reed] the way through then he went on and overtook his party, and Reed returned to his. Just then we overtook and joined the Donner Party. Here is what caused our suffering, for Reed told us if we went the Canon road we would be apt to break our wagons and kill our oxen, but if we went the new way, we could get to Salt Lake in a week or ten days

This is also the account told by Lovina Graves, who was 12 in 1846, to her granddaughter Enda Maybelle Sherwood, who published the story in the San Francisco Chronicle about 1900. As it happens, Lovina was married in 1855 to John Cyrus, who had also emigrated in 1846, but with the Pyle family of the Harlan-Young Party, as mentioned by Lovina.

Grandma’s people came on toward California and overtook the Donner Party about four days travel with heavy wagons from Fort Bridger. The captain of the Donner Party was then seeking the new road or shortcut to California, when they overtook heavy wagons from his company. It was not exactly a short-cut they were seeking, but an easier and more pleasant road. Their plan was to avoid the steep and disagreeable Weaver canyon. Grandpa Cyrus came to California just a few days ahead of the Donner Party, but through the Weaver canyon. He said that they had to lift their wagons over boulders and even over fallen trees in coming through the canyon, this road was so rough.

Tuesday, August 11, 1846

Tues 11 left Camp and took the New rout with Reed as Pilot he having examined the mountains and vallies from the south end of the Lake this day made 5

[Their new road followed the route of present Utah Highway 65 through Main Canyon to a camp at the springs in Dixie Hollow, near the present junction of Utah Highways 65 and 66.]

Wednesday, August 12, 1846

Weds 12 left Camp late and encampe on Bosman Creek on new rout made 2

[The creek was called Bauchmin’s Creek at the time, it is now called East Canyon Creek. This camp was near the present East Canyon State Park.]

Thursday, August 13, 1846

Thurs 13 Made a New rout by Cutting willow Trees & on Basman Creek 2

Friday, August 14, 1846

Frid 14 Still on Basman Creek and proceeded up the Creek about one mile and Turned to the right hand up a Narrow valley to Reeds Gap and encamped about one mile from the mouth making this day 2 Spring of water

This camp was in the present Little Emigration Canyon, along Utah Highway 65. Reed’s Gap is a low point on the Wasatch crest, south of the present Big Mountain, 8,763’. This pass was crossed by the Mormons in 1847 and called Pratt’s Pass.

Saturday, August 15, 1846

Sat 15 in Camp all hands Cutting and opning a road through the Gap

Sunday, August 16, 1846

Son 16 Still Clearing and making Road in Reeds Gap.

Virginia Reed, in her 1891 memoirs in Century Magazine, remembered:

Only those who have passed through this country on horseback can appreciate the situation. There was absolutely no road, not even a trail. The canon wound around among the hills. Heavy underbrush had to be cut away and used for making a road bed. While cutting our way step by step through theHastings Cut-off,we were overtaken and joined by the Graves family, consisting of W.F. Graves, his wife and eight children, his son-in-law Jay Fosdick, and a young man by the name of John Snyder.

In his article of March 25, 1871, in the Pacific Rural Press, Reed recounts: The afternoon of the second day, we left the creek turning to the right in canyon leading to a divide. Here Mr. Graves and family overtook us.

As noted, the Graves family remembers joining the Party just as Reed had returned from his meeting with Hastings. See Entry for August 10.

Monday, August 17, 1846

Mon 17 Still in Camp and all hands working on the road which we finished and returned to Campe

Tuesday, August 18, 1846

Tus 18 this morning all started to Cross the Mountane which is a Natural easey pass with a little more work and encamped making this day--5 J F Reed Brok and axle tree

This pass below Big Mountain was improved by the Mormon pioneers the next year, and is still in use today as Utah Highway 65. The camp was in present Little Emigration Canyon.

Reed, in his 1871 memoirs, recalled that the first accident that had occurred was caused by the upsetting of one of my wagons,

which could be the same accident as this broken axle.

Thornton, based on Eddy’s recollections, wrote that on September 4th, after the Party had reached the Salt Lake, Here Mr. Reed broke an axletree, and they had to go a distance of fifteen miles to obtain timber to repair it. By working all night, Mr. Eddy and Samuel Shoemaker completed the repair for Mr. Reed.

Reed’s diary makes no mention of this incident, so it is possible Eddy and Thornton were mistaken. Stewart, writing in 1936 before the discovery of the Miller-Reed diary, follows Thornton.

Wednesday, August 19, 1846

Weds 19 this day we lay in Camp in a neat little valley fine water and good grass the hands ware this on the other on West Side of Small mountain in a Small Valley Clearing a road to the Valley of the Lake we have to Cross the outlett of the Utah Lake on this Rout near the Salt Lake

[This camp was in Mountain Dell, on the present Parley’s Creek above the site of the present reservoir.]

Parley’s creek flows straight down to the Salt Lake Valley, and Hastings had ascended it on his way east to meet the emigrants. Pike and Stanton, who had accompanied Reed to overtake Hastings, also followed Parley’s creek on their return, and found the Party at Mountain Dell.

Thornton wrote that Pike and Stanton were lost in the Wasatch, and that the Party had sent out a search party. In Mountain Dell,

Messrs. Stanton and Pike, who had been lost from the time Mr. Reed had gone forward with them to explore, were found by the party that had been sent to hunt for them. These men reported the impracticability of passing down the valley in which they then were; and they advised their companions to pass over a low range of hills into a neighboring valley. This they did.

This low range of hills was Little Mountain, to the north of Mountain Dell, and it led into Emigration Canyon. The pack trail down the creek from Mountain Dell was not opened as a wagon road until 1850, by Parley Pratt, and is the present route of Interstate 80 into Salt Lake City. The Donner’s route down Emigration Canyon is the route of present Emigration Canyon Road, and was the main road to Salt Lake City through the 1860’s.

Thursday, August 20, 1846

Thurs 20 Still in Camp and hands Clearing Road

In his 1871 article in the Pacific Rural Press, Reed responded to the criticism of this route:

During this time the road was cleared for several miles ahead. After leaving this camp the work on the road slackened and the further we advanced the slower the work progressed. I here state that the number of days we were detained in road-making was not the cause by any means, of the company remaining in the mountains during the following winter.

Friday, August 21, 1846

Frid 21 this day we left Camp Crossed the Small Mountain and encapd in the vally runig into the Utah outlett making this day 4

[The pass is present Little Mountain Summit on Utah Highway 65. The camp was in Emigration Canyon, along the present Emigration Canyon Road.]

Pack Train Descending Emigration Canyon to Great Salt Lake

Saturday, August 22, 1846

Sat 22 this day we passed through the Mountains and encampd in the Utah Valley making this day 2

This final crossing of the Wasatch contained one more challenge for the Party. As John Breen told Eliza Farnham, who published the story in her 1856 book California, In-doors and Out:

We at last came within one mile of Salt Lake Valley, when we were compelled to pass over a hill so steep that from ten to twelve yoke of oxen were necessary to draw each wagon to the summit. From this height we beheld the Great Salt Lake, and the extensive plains by which it is surrounded. It gave us great courage; for we thought we were going to have good roads through a fertile country;

As remembered by Virginia Reed in 1891:

Finally we reached the end of the canon where it looked as though our wagons would have to be abandoned. It seemed impossible for the oxen to pull them up the steep hill and the bluffs beyond, but we doubled teams and the work was, at last, accomplished, almost every yoke in the train being required to pull up each wagon. While in this canon Stanton and Pike came into camp; they had suffered greatly on account of the exhaustion of their horses and had come near perishing.

Virginia’s account that Pike and Stanton had not returned until after the Party had already decided to cross to Emigration Canyon contradicts Eddy’s account (via Thornton) that it was Pike and Stanton who advised the Party to follow that route.

As for that final bluff that the Donners surmounted, the Mormon emigrants the next year did not even attempt it. With greater manpower, they cut the road along the canyon bottom. It is a measure of the Donner Party’s weariness of the ax and pick that they chose instead to haul their wagons over the bluff, now called Donner Hill. The Donner’s entered the Valley on the south side of Emigration Canyon. On the north side today is the This is the Place Monument, which commemorates the location that Brigham Young told the pioneers that This is the place.

In fact, the Mormon road also was on the south side of the canyon. The monument contains a plaque honoring the Donner Party’s work in opening the route.

Plaque on This is the Place Monument

Sunday, August 23, 1846

Son 23 left Camp late this day on acct. of having to find a good road or pass through the Swamps of the utah outlet finally Succeeded in and encampd on the East Bank of Utah outlett making 5

[This camp was probably near present Parley’s Creek, near 11th East and 21st South.]

In his1871 article in the Pacific Rural Press, Reed wrote: We progressed our way and crossed the outlet of the Utah, now called the Jordon, a little below the location of Salt Lake City.

This crossing was near present South Salt Lake, approximately 2700 South Street, about 4 miles south of the Temple Street ford used by some of the Harlan-Young party.

Monday, August 24, 1846

Mo 24 left our Camp and Crossed the plain to a spring at a point of the Lake mountain and 1 1/2 miles from the road traveled by the people who passed the Cannon 12 Brackish water it took 18 days to get 30 miles

[The camp was near present Lake Point, Utah.]

In his 1871 article in the Pacific Rural Press, Reed wrote From this camp in a day’s travel we made connection with the trail of the companies that Hastings was piloting through his cutoff. We then followed his road around the lake...

The diary entry about taking 18 days to travel 30 miles was Reed’s later-added margin comment. Reed thus accounts for 18 days spent making the road across the Wasatch to avoid the Weber Canyon descent taken by Hudspeth and the Harlan-Young wagons. Reed under-estimated the mileage, as his own diary entry mileage adds to 39. He repeated his estimate of the time to George McKinstry, who reported in a letter dated February 13, 1847 to the California Star: and Mr. Reed and others who left the company, and came in for assistance, informed me that they were sixteen days making the road, as the men would not work one quarter of their time.

Reed also reported this estimate in his report paraphrased in the Illinois Journal of December 9, 1847: After traveling eighteen days they accomplished the distance of thirty miles, with great labor and exertion, being obliged to cut the whole road through a forest of pine and aspen.

James Mathers, who left his original party at Bridger’s Fort, caught up to the Harlan wagons at the Bear River, and reached the entrance of the Weber River canyon on July 29, 1846. He reached the Utah outlet on August 7th, for a total of ten days. Like the Donners, the Harlan Party spent some time in camp while members explored alternate routes. Taking Reed’s account as accurate, the detour over the Wasatch delayed the Donner Party by eight days.

Other accounts ascribe more time lost to the crossing of Big Mountain. Thornton’s account, based on Eddy’s recollections, describes the crossing of the Wasatch and concludes They were thus occupied thirty days in traveling forty miles.

Thornton’s estimate of mileage is closer to the actual distance of 35 miles from Henefer to Salt Lake, measured by the Mormon Roadometer

of 1847.

John Breen in his Pioneer Memoirs

of November 19, 1877, wrote that:

...we left the old emigrant road that passed on the North side of the Great Salt Lake and by the advice of a man named Hastings undertook to find a rout by the south side. Here our real troubles began, we were delayed for near a month in the timbered canions to the East of the lake, where there was little feed for stock

More important than the lost time was the physical and psychological cost of cutting the road and enduring the mutual resentment between those who chose the route and those who had to cut it out of the woods.

Tuesday, August 25, 1846

Tues 25 left Camp early this morning intending if possibl to make the Lower wells being fair water 20 which we made and in the evening a Gentleman by the name of Luke Halloran, died of Consumption having been brough from Bridgers Fort by George Donner a distance 151 Miles we made him a Coffin and Burried him at the upper wells at the forks of the road in a beautiful place fair water

The Trail followed the general course of present Utah Highway 138 to near Grantsville, Utah. They passed Adobe Rock in Tooele Valley, described by Bryant as several remarkable rocks rising in tower-like shapes from the plain, to the height of sixty or eighty feet.

In his 1871 article in the Pacific Rural Press, Reed wrote:

We then followed [Hasting’s] road around the Lake without incident worthy of notice until reaching a swampy section of the country west of Black Rock, the name we gave it. Here we lost a few days on the score of humanity. One of our company, a Mr. Halloron being in a dying condition from consumption. We could not make regular drives owing to his situation. He was under the care of Mr. Geo. Donner, and made himself know to me as a Master Mason. In a few days he died. After the burial of his remains we proceeded on our journey, making our regular drives, ...

Thornton, based on Eddy’s recollection, wrote that:

About 4 o’clock, P.M., Mr. Hallerin, from St. Joseph, died of consumption, in Mr. George Donner’s wagon. About 8 o’clock, this wagon (which had stopped) came up, with the dead body of their fellow traveler. ...

Adobe Rock, east of Grantsville, UT, photographed 1999

Wednesday, August 26, 1846

Wed 26 left Camp late and proceed to the upper wells One of them delightful water being entirely fresh the rest in No about 10 all Brackish this day Buried Mr Luke Halloran hauling him in his Coffin this distan 2 which we only mad and Buried him as above stated at the forks of the One

Turning directly South to Camp the other west or on ward

The upper wells were south of the Lake, at present Grantsville, Utah. Grantsville is the home of the Donner-Reed Museum, which contains artifacts recovered from the Salt Desert.

James Breen, in a letter to C.F. McGlashan in about 1878, described the burial:Halloran’s body was buried in a bed of almost pure salt, beside the grave of one who had perished in the preceding train. It was said at the time that bodies thus deposited would not decompose, on account of the preservative properties of the salt. Soon after his burial, his trunk was opened, and Masonic papers and regalia bore witness to the fact that Mr. Halloran was a member of the Masonic Order. James F. Reed, Milton Elliott, and perhaps one or two others in the train, also belonged to the mystic tie.

Thornton described the burial:

The day ... was spent, with the exception of a change of camp, in committing the body of their friend to the dust. They buried him at the side of an emigrant who had died in the advance company. The deceased gave his property, some $1500, to Mr. George Donner.

The amount was verified by a note found in the Miller-Reed Diary when it was donated to Sutter’s Fort in 1945. The note lists A Statement of Breen & Halloran/Stock of Merch, etc., taken June 25th - 1845

and lists Halloran’s stock as $1,435.

It is not known who took this stock, and it is likely that the name Breen

refers to a different Breen than Patrick Breen.

Luke Halloran thus became the first casualty of the Donner Party. The other emigrant who was buried at the fork of the road was John Hargrave who had died on August 11, as recorded in Heinrich Lienhard’s diary.

Thursday, August 27, 1846

Thur 27 left early this day and went west for half the day at the foot of the Lake Mountains the latter 1/2 of the day our Course S.W. to a No of Brackish Wells making 16 miserable water

[This day the Party rounded the Stansbury Mountains (at present Timpie, UT) and camped at Burnt Spring in the north end of Skull Valley.]

Burnt Spring, Timpie, UT, photographed 1999

Hastings Trail near Lone Rock in Skull Valley, photographed 1999

Friday, August 28, 1846

Frid 28 left Camp and glad to do so, in hopes of finding fresh water on our way but without Success until evening when it was time to Camp Came to a No of delightful fresh water wells this Camp is at the Most Suthern point of the Salt Lake 20 miles Northwest we commence the long drive we are taking in water, Grass, and wood for the various requirements 12

This camp was at Hope Wells, at Iosepa, one of the springs along the west side of the Stansbury Mountains in present Skull Valley. These wells were fondly recalled by the Donner Party. Virginia Reed, in her 1891 memoirs, wrote:

We were now encamped in a valley calledTwenty Wells.The water in these wells was pure and cold, welcome enough after the alkaline pools from which we had been forced to drink.

According to Thornton,

they resumed their journey, and after dark encamped at a place to which they gave the name of the Twenty Wells. The name was suggested by the circumstances of there being at this place that number of natural wells, filled to the very surface of the earth with the purest cold water. They sounded some of them with lines of more than seventy feet, without finding bottom. They varied from six inches to nine feet in diameter. None of them was overflowed; and, what is most extraordinary, the ground was dry and hard near the very edge of the water, and upon taking water out, the wells would instantly fill again.

Reed’s diary and these other accounts appear to confuse two different wells. According to Morgan and Stewart, Twenty Wells is the site of present Grantsville on the east side of the Stansbury Mountains. These wells are shown on T.H. Jefferson’s map as Hastings Wells.

Reed called these the Upper Wells,

and says that only one was fresh water, the rest brackish. By contrast, Reed describes the wells at the beginning of the dry drive as all fresh. These are shown on Jefferson’s map as Hope Wells

in Skull Valley on the west side of the Stansbury Mountains.

James Mathers describes the wells on the east side of the Stansbury Mountains: There are a great many beautiful Springs but the water is, in many of them, strongly impregnated with salt.

The next day, Mathers Remained in camp--had good grass in abundance and numerous springs, or rather pits, of good water....

Thornton describes a days’ march beyond Twenty Wells to another set of similar wells in a large and beautiful meadow. ... Here they found a letter from Lansford W. Hastings, informing them that it would occupy two days and nights of hard driving to reach the next water and grass.

Eliza Donner Houghton wrote in her 1911 book The Expedition of the Donner Party:

Then came a long, dreary pull over a low range of hills, which brought us to another beautiful valley where the pasturage was abundant, and more wells marked the site of good camping grounds.

Close by the largest well stood a rueful spectacle,-- a bewildering guide board, flecked with bits of white paper, showing that the notice or message which had recently been pasted and tacked thereon had since been stripped off in irregular bits.

In surprise and consternations, the emigrants gazed at its blank face, then toward the dreary white beyond. Presently, my mother knelt before it and began searching for fragments of paper, which she believed crows had wantonly pecked off and dropped to the ground.

Spurred by her zeal, others also were soon on their knees, scratching among the grasses and sifting the loose soil through their fingers. What they found, they brought to her, and after the search ended she took the guide board, laid it across her lap, and thoughtfully began fitting the ragged edges of paper together and matching the scraps to marks on the board. The tedious process was watched with spellbound interest by the anxious group around her.

The writing was that of Hastings, and her patchwork brought out the following words:

2 days -- 2 nights -- hard driving -- cross -- desert -- reach water.

As Eliza was only four in 1846, she may have relied on Thornton and family legends when writing the story sixty years after the event.

Thornton and Houghton may have been confused about the letter from Hastings. This letter is not mentioned by James Reed in any of his accounts, nor by Virginia Reed. James Reed had caught up to Hastings on August 9 near the point of the lake. Hastings probably told Reed directly about the dry drive then. Hastings and the Harlan-Young Party made the dry drive from August 17-22. Certainly Hastings had not re-crossed the dry drive to provide new information in a letter. Perhaps Thornton and Houghton confused the story of Hasting’s earlier letter at the Weber River canyon.

Saturday, August 29, 1846

Sat. 29 in Camp wooding watering and laying in a Supply of grass for our oxen and horses to pass the long drive which Commene about Miles We have one encmpmt between but neither grass wood or water of sufficentt quallity or quantity to be procured water Brackish Sulphur, grass Short and no wood-

Reed’s entry about water Brackish

appears to be a reference to the springs at the next encampment, as this contradicts the previous day’s entry that the camp of the 28th and 29th contained a No of delightful fresh water wells.

This is more evidence that Reed updated his diary entries a day or more after the events.

Sunday, August 30, 1846

Son 30 Made this day 12 to a Silphur Spring in the Mountain which ought to be avoided water not good for Cattle, emigrants should keep on the edge of the lake and avoid the Mountain entirely here commenced the long drive through the Salt desert.

The Trail crossed Skull Valley from the springs along the western base of the Stansbury Mountains, to Redlum Spring in the Cedar Mountains. The Trail can be seen just north of Henry Spring Road.

Trail Across Skull Valley, photographed circa 1930

Redlum Springs, photographed 1999

Monday, August 31, 1846

Mon 31 in desert drive of Sixty 60 miles

Reed suggested not crossing the Cedar Mountains via Hastings Pass, but instead skirting the base of the mountains towards a lower pass to the north. This is the pass where present Interstate 80 crosses the Cedar Mountains west of Rowley Junction. Reed may have been motivated by the difficulty of crossing Hastings Pass, as indicated by T.H. Jefferson on his map: East to west side Scorpion Mt., 9 miles. Road, steep hills, some sideling, rather bad.

Trail to top of Hastings Pass, photographed 1999

The Trail headed northwest from Hastings Pass, crossing present Interstate 80 near the Aragonite exit, and then crossed the Gray Back Hills just north of present Interstate 80.

View of Gray Back Mountains, Salt Desert and Pilot Peak, from Hastings Pass, photographed 1999